By Mike NOTE: This post has some serious inaccuracies and overwroughtness; I’ll be altering it in the next couple of days.

There’s some buzz about a new study in the International Journal of Biological Sciences, which states that the studies Monsanto used to justify the use of three varieties of genetically modified corn are flawed.

Thing is, in another life I’m a medical writer (mostly whoring for the drug companies, but that’s a story for another time), which means long bitter years of experience reading medical articles, so I figured I’d take a look and see if I could make sense of what’s going on.

The basic facts:

- To meet EU requirements, Monsanto did studies on three strains of genetically modified corn (MON 810, MON 863, NK 603). Rats were given the GM corn (11% or 33% of their diet) or control corn for three months.

- The studies were done by an independent lab, but the data were analyzed and interpreted by Monsanto researchers, who concluded that the corn was safe.

- Greenpeace funded a reanalysis of the data of one study, and then another reanalysis of all three, which is the study that’s getting the attention. These reanalyses found problems with Monsanto’s analysis and conclusions, and found several statistically significant effects of the GM corn.

- The first reanalysis was in turn contradicted in Douro et al by an expert panel, which didn’t include Monsanto employees but may have been paid for by Monsanto (I don’t have access to the full article).

Some criticisms of the Greenpeace reanalyses, in descending order of compellingness (imho), are:

The Greenpeace authors cherrypick statistical significance. “Statistical significance” is when a given result is very unlikely and therefore can be treated as if it didn’t happen by chance. (If you lose to a royal flush, that’s bad luck. If you lose to three royal flushes in a row, it’s time to start stabbing). The conventional cutoff between “random noise” and “real effect” is the .05 significance level, which means that a result is considered significant if it would only happen by chance 5% of the time or less. The corollary is that 5% of truly random results will be statistically significant, so if you look at 500 variables, around 25 of them will be statistically significantly different just by chance. Looking only at these 25 variables (which is, in effect, what the Greenpeace researchers do) is misleading.

The effects they note are often not dose dependent. For instance, female rats with 11% of their diets made up of MON 810 corn lost kidney weight, but female rats whose diet was 33% MON 810 corn didn’t. Intuitively, if you’re eating a poison, more should be worse, and if it’s not, maybe it’s not a poison. The Greenpeace authors say:

- Many of the effects are in fact dose dependent

- Effects on metabolism are not always expected linear with dose

- With only two doses studied, it’s hard to establish a dose effect

The effects are often not time dependent. The rats were evaluated at 5 and 14 weeks; many effects that were seen at week 5 were not seen at week 14. Although intuitively, 14 weeks of a poison should be worse than 5 weeks, it’s actually entirely conceivable (imho) that early effects would be more dramatic than later ones. If you suddenly started drinking a fifth of vodka a day, it would lay you flat on your back the first day, but after a while your body would adjust until the vodka finally destroyed your health years later. (For that matter, if I remember Super Size Me correctly, Morgan Spurlock’s vital signs went way out of whack early on and then improved somewhat as he got used to a crap diet.)

Many of the results were not demonstrated in both sexes. This is where the Greenpeace researchers make a reasonably compelling case: they say there are in fact clear sex-specific effects, which is what you would expect from a substance that has effects on sex hormones, as many substances do (although the original study didn’t look for hormonal effects themselves).

Still, some of the criticisms are valid; the Greenpeace researchers are clearly, in at least some cases, torturing the data until it confesses. So who do we believe?

Drum roll please:

The Greenpeace authors.

The Greenpeace authors’ main conclusion isn’t that Monsanto’s corn is harmful. It’s that the data don’t prove Monsanto’s corn is not harmful. Which is 100% true. Monsanto’s studies were too small, and too short, to prove anything except that GM corn can be fed to a small number of rats for three months without immediately killing them. Long-term effects? Cancer? Reproductive effects? Birth defects? These studies prove nothing either way. (Heck, if you gave a small number of rats cigarettes for three months, you might not find any cancers.)

And the burden of proof should be on Monsanto. Two of the three strains tested—and I find this simply incredible—have been modified to express a toxin as an insecticide. So instead of dumping pesticide on the food (which is generally not the best idea), Monsanto has put pesticide in the food. The fact that many countries have allowed this to happen at all is bizarre on the face of it. The fact that they let it happen on the basis of one small rat study per strain is insane.

As I said, I’m familiar with pharmaceutical studies; when a pharmaceutical is tested, small studies on animals are just the first step. Everyone in medicine understands that a drug that seems safe at first may turn out to be deadly, a result in one small study may disappear in the next, effects in rats may not hold true for humans, and so on. In real medicine, anyone who drew broad conclusions from a small rat study, or even a few rat studies, would be laughed out of the profession. And yet Monsanto does just that. Here’s the conclusion of the original MON 810 study:

This study complements extensive agronomic, compositional and farm animal feeding studies with MON 810 grain, confirming that it is as safe and nutritious as grain from existing commercial corn varieties.

There is simply no way that conclusion is warranted by the data. (For the record, the expert panel didn’t go nearly so far—they merely said that neither the original studies or the first reanalysis gave conclusive evidence of problems, which is true as far as I can tell.)

Now: there’s another study, undertaken by the Austrian government, that did much better—it studied several generations of rats, and while it found that GM corn had an effect on reproduction in the third and fourth generations (a result that has been criticized), the study is remarkable for all the problems it didn’t find—for instance, rats fed GM corn actually lived slightly longer than the other rats (although that was probably statistical noise, it still means that GM corn is unlikely to shorten a rat’s life).

So the point is not that GM corn is horrible; the point is that things like this should really be studied a lot better before we release them into the environment and the food supply. If these strains really are harmless, that only means we got lucky this time.

And anyway, if Monsanto really believes that GM corn’s safety has been proven, why not do a legit study to confirm it? One obvious possibility is that Monsanto is not nearly as confident as it pretends to be; and simply doesn’t want to know what a real study would reveal.

But I do.

PS: I was basically done with this post when I read this, which makes many of the same points with a different take on them. My only disagreement is with the idea that the funding source calls the Greenpeace results into question. Or rather, I don’t disagree with that at all (which is why I called them the “Greenpeace authors”), but the fact is, the same thing applies when Monsanto is funding a study. What’s needed is truly independent analysis.

By Mike It’s hard to see how the Haitian earthquake could be worse–a powerful quake, close to the surface, striking right in a densely populated area. But this is even harsher than what you might think: I did some freelance aid work in India after the 2004 tsunami, and the devastation was very much proportional to the poverty of the area before the wave hit. We (me and some Indians I fell in with) were giving aid in Nagapattinam, in Tamil Nadu (a backward state by Indian standards), and when we were done for the day we would drive up to Karaikal, in Pondicherry state, which is far better off and where the damage was already fixed up and the restaurants were open.

Point being, the devastation in Haiti will be magnified by the fact that Haiti is badly off even by the standards of the third world. Haiti has cut down its forests (to the point that you can see the border on a satellite picture–green on the Dominican side, brown on the Haitian side), and it’s been so poor for so long that society has started to break down; here’s Yolette Etienne, an aid worker, quoted in the book Planet of Slums:

Now everything is for sale. The woman used to receive you with hospitality, give you coffee, share all that she had in her home. I could go get a plate of food at a neighbor’s house; a child could get a coconut at her godmother’s, two mangoes at another aunt’s. But these acts of solidarity are disappearing with the growth of poverty. Now when you arrive somewhere, either the woman offers to sell you a cup of coffee or she has no coffee at all. The tradition of mutual giving that allowed us to help each other and survive—this is all being lost.

And now this.

What happens when a disaster strikes a place where “the tradition of mutual giving” is gone? Will Haitians pull together? Will the country simply fall apart?

By Mike Well, if you’ve ever wondered what happens to plastic, this is what happens.

I should probably write about the economic concepts this illustrates, like externalities and bla bla bla, but really, I’ll shut up so you can go look at the pictures.

Okay, one more thing: bottle tops are like half the volume of plastic in these photos. I’m always recycling plastic bottles but not bothering to recycle the top. . . .

(Credit for pointing this out in the first place goes to Ethicalreasoning on Reddit).

By Mike Here’s a slideshow interspersing pictures of the Great Depression with pictures of the crisis today. Worth a look.

By Mike The most gratifying part of paying attention to the economy is watching, at the end of every bubble, almost as a natural part of the financial cycle, the predictable spate of arrests.

There’s Madoff, of course, but his Ponzi scheme seems to have been a one-off (unless you think the whole stock market is a Ponzi scheme, which makes sense—after all, the problem with a Ponzi scheme is that nobody can take a dollar out that wasn’t put in by someone else, and that’s true of the stock market as well). More typical, though, are the arrests of insider traders.

What is insider trading? Let’s review the case of Martha Stewart, just because she’s famous: Some years ago, she sold her ImClone stock when the CEO of the company—who happened to be her friend—told her that they were about to publicly announce a big setback. She avoided losing money when the stock plummeted, which sounds good except the sucker who bought her stock—who we’ll call Shmo—took Stewart’s loss, for no better reason than Stewart was buds with the CEO and Shmo was not.

EDIT: Normdeplume, at Daily Kos, where I sometimes crosspost under the name manfromporlock, points out that I had my facts a bit wrong; the CEO’s involvement was never proven (in Stewart’s case, at least–he was guilty of other things). Shouldn’t go trusting my memory. /EDIT

The problem is obvious—insider trading makes Wall Street a way for people who are already rich and well-connected to fleece the Shmos of the world. And that’s why the government steps in and sends insider traders to jail, right?

Well, not exactly. A few high-profile arrests after a bubble pops—Stewart, Michael Milken way back when, the ones today—don’t make sense as a way to prevent insider trading. If that was the point, the arrests would come during the bubble (when the crimes are usually taking place) and there would be a lot more of them.

The way we do things does make sense as a way to restore public faith in a shaken system. Which sounds good, but think about it: these arrests are designed, not to prevent us from being fleeced (which is what we worry about), but to stop us from taking our money and going home (which is what Wall Street worries about).

Still, let’s put that aside and imagine a perfect system where every insider trader is quickly caught and punished. In that system, insiders will still fleece shmos, and there’s no way to stop it.

That’s because an insider’s tip to sell a stock is also a tip to not buy that stock. And a tip to buy a stock is also a tip to not sell it. So even if Martha Stewart had dutifully held on to her ImClone stock, she might well have still benefited from the CEO’s tip if she’d been planning to buy more. But she would have stayed a free woman, because there’s no way to prove—or even to know—what she planned.

Now: when I first thought of “insider nontrading” I believed it was a new term and a new insight, and was all proud of myself, but as with most original thoughts it turns out that others beat me to it. Still, it’s not widely understood, and it’s worth stressing because it means that over the long run we shmos who buy stocks right before they drop and sell them right before they pop will always lose to insiders, who know not to do these things simply because they’re on the inside and we’re not. It’s time to take our money (those of us who still have any) and go home.

By Mike I enjoy Photoshop Disasters, a blog that is exactly what the name says, but this post struck me for a completely different reason than the freaky arms.

What struck me: the young woman’s look of accomplishment, of satisfaction, of sheer thrill.

In an ad for a bank.

Yeah, it’s just a silly ad. But really, it goes to the very heart of the modern economy. In the textbooks, we want things (food, shelter, shoes, banking services), and sellers compete to satisfy these wants. They compete either by making a better product or selling the same product at a lower price.

But more and more of our economy doesn’t work that way. Rather, sellers make a product that is barely distinguishable from its competition either in quality or price, and then they dress it up as something completely different in order to sell it.

So a Starbucks coffee, once it’s gone through the advertising machine, becomes a cup of meaning; a sneaker becomes an act of rebellion, a bottle of soap becomes pure, liquid elegance, and so on. I recently saw a car ad that said, in its entirety, “Misery has enough company. Dare to be different,” managing to sell happiness, daring, and distinction in a single sentence. [Edit: Or, um, two sentences. Sometimes I am a moron.]

And the fact is, these ads work. Look at the woman with the mutant arms again. Who doesn’t want to feel like that? And even though we know intellectually that all the ad is actually offering is ordinary ATMs, some of us really will switch banks, hoping on some level to get some of that woman’s ecstasy for ourselves.

Of course, switching banks will leave us no more ecstatic than before. Buying the car–which is, after all, produced in the millions–will leave us with the same amount of happiness, daring, and distinction we started with.

I have no grand conclusion here; my point is just that the economy is truly screwed up in ways that can paradoxically escape our notice because they’re so familiar. And the first stage in fixing the economy is seeing it for what it is.

By Mike Well, my legions of admirers–most of whom can hardly contain their incoherent praise of Viagra (seriously: grammar counts, even if you’re a spambot) should be happy to know that I’m back. I was away dealing with a bit of a financial situation; unlike many, mine actually had some larger economic significance, so I’ll post about that (and about life in the cubicle mines, which I’d managed to avoid for years) soon.

By Mike Well, as I’ve been saying, things seem to be getting better (or at least getting worse more slowly). But it looks like we could be in for another meltdown in a year or two. Adam Levitin shows how this time it won’t be subprime mortgages, but “option ARMs.” Option ARMs give consumers the choice of how much to pay in a given month, and the low option is typically less than the accrued interest that month (so the mortgage grows). Like subprime loans, these seemed like good ideas when every moron in finance (which is to say, pretty much everyone in finance) “knew” that real estate prices would rise forever. After all, if you buy a house with a $200,000 mortgage, it’s okay for the mortgage to grow to $220,000 if the house’s value rises to $400,000. But of course, today that $200,000 house will bring only $100,000, and these mortgages generally have provisions where they reset–that is, the minimum payment shoots up–if they go too far underwater. The tiny little chart in Levitin’s post is worth clicking on–it shows how many option ARMs will be resetting in the next few years. Summary for the very busy: it’s about as many as the number of subprime loans that reset in 2007-8, which triggered the whole meltdown in the first place. Joy.

(Creditslips via Consumerist.)

EDIT in early 2012: Well, that didn’t happen.

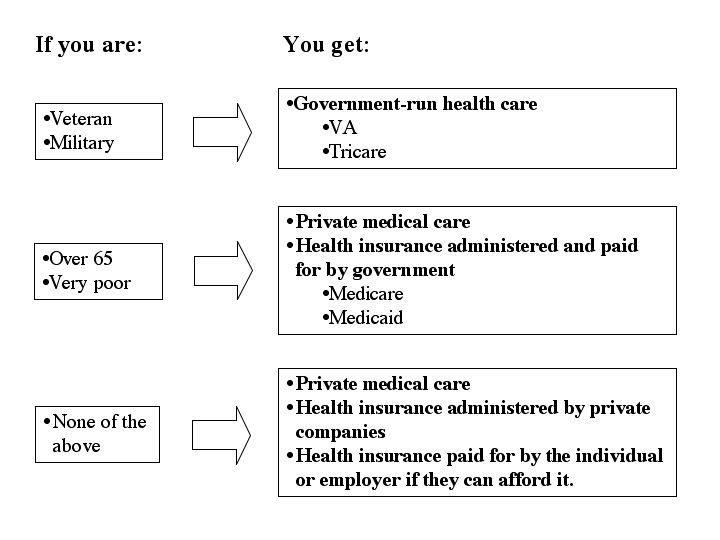

By Mike Okay, so I read the entire freaking health care bill (the July 14 version). Here’s a summary, along with some suggestions how to make it better. Yeah, it’s long, but it’s less than 1% of the original, so there’s that.

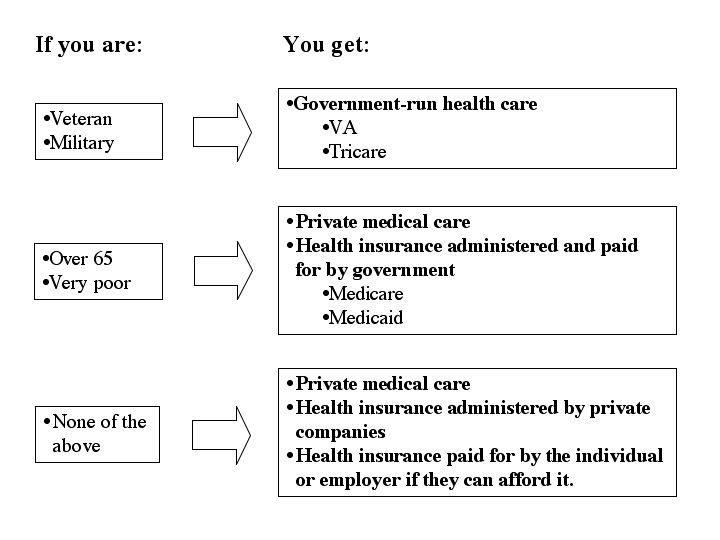

First, here’s our current system, in a handy-dandy chart (unfortunately Dan is busy illustrating the book, so you get my PowerPoint graphics).

Rube Goldberg would find much to like in this system, but many of its parts work okay. The big problem is the last bit—people who aren’t eligible for VA, military care, Medicare, or Medicaid. Private health insurance is good in theory, but in practice:

- It’s inefficient—for-profit companies must provide a profit to their shareholders. So all else being equal, that they must charge more and pay out less than a government-run entity or not-for-profit company.

- Given that their goal is profit, they must do their best to exclude sick people, deny claims, and drop you if you get sick. So a lot of private health insurance is “junk insurance,” where insurers efficiently take money without actually providing benefits.

- Given the high rate of denials, doctors and hospitals must maintain extra people on staff to fight to be paid. These extra salaries increase overall health care costs.

- And anyway, not everyone who needs private health insurance can afford it. To the tune of 40-odd million people.

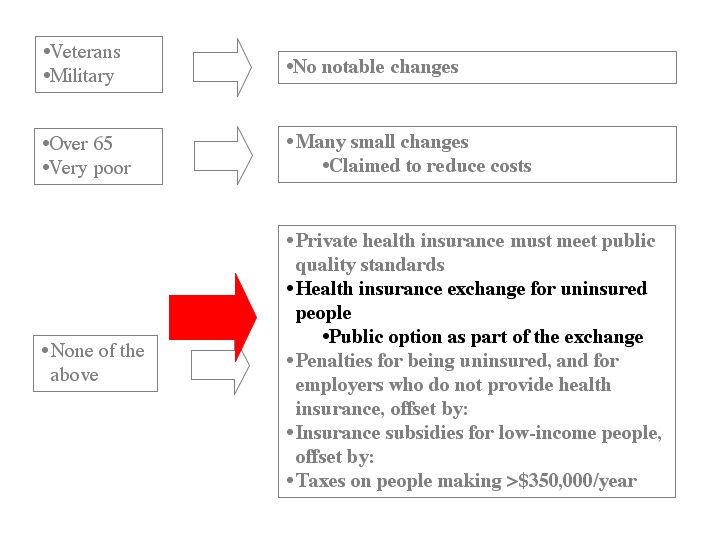

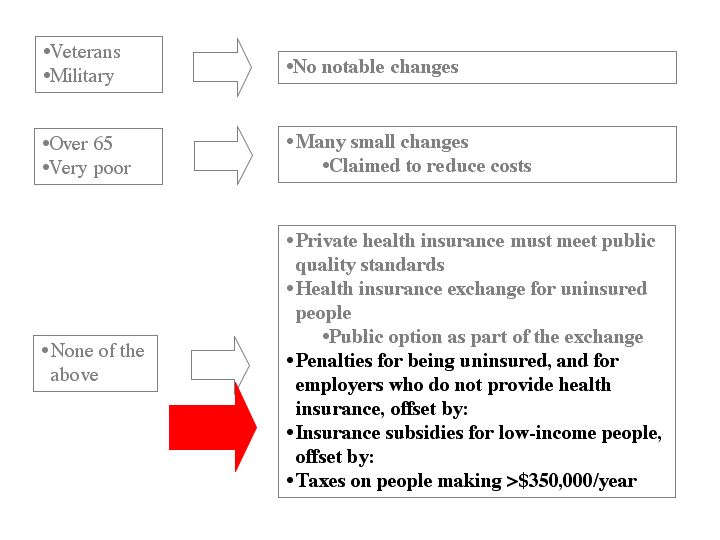

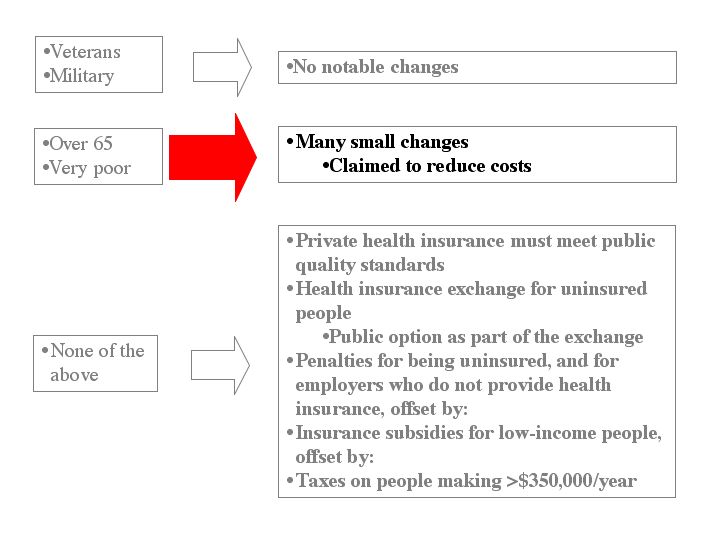

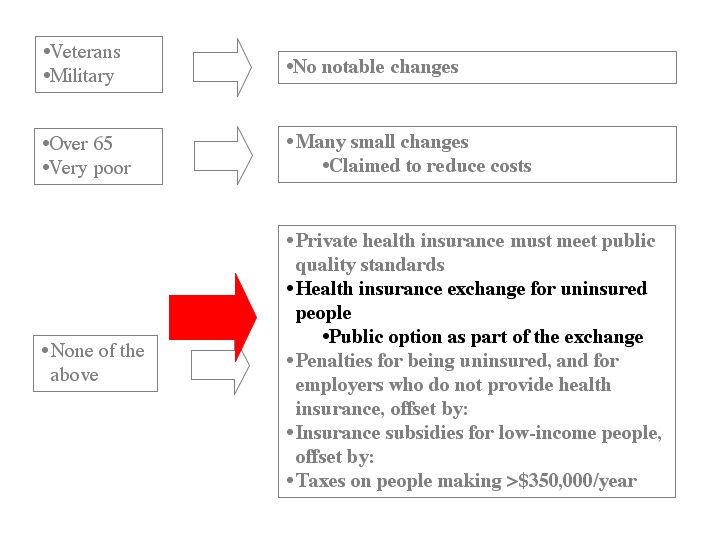

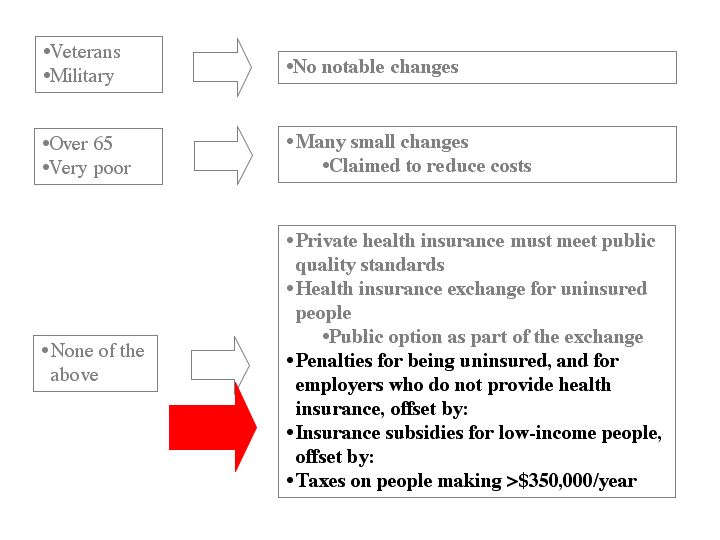

So that’s the situation. Here’s what the current plan will do:

I’ll look at these parts separately, but before I do I’ll repeat a point I made in a previous post: most of this program doesn’t go into effect until 2013, and then there’s a five-year grace period for existing employer-based plans. So if you have a junk insurance plan, it might not stop sucking unholy rocks until 2018, which is more than enough time for lawyers and lobbyists to whittle reform away to nothing. And then the insurance company could choose to “grandfather” your plan, which means that it keeps the old terms but can’t take new people.

Which makes all the “we can’t wait” talk a bit odd–we’re going to wait. Obama, in his speech, said that the four-year delay “will give us time to do it right.” That’s just silly—four years was enough time to build a military from scratch and win World War II with it. And a five-year grace period after that? If the health insurers are really so incompetent that they need nine years to fix their plans, they have no business existing.

So that’s the first big way to improve this bill—there’s no reason not to make Year 1 of this bill 2011 rather than 2013, with no grace period for existing plans and no grandfathering after, say, three more years.

As I’ll detail below, there are some provisions that go into effect earlier than 2013, including some important ones (and one indefensible giveaway to the insurers).

Now, let’s take a look at specifics, starting with:

This is the meat of the bill, and there’s some really good stuff here.

Section 111 says that plans can’t exclude people based on pre-existing conditions. That’s big.

Section 112 says that plans must issue you insurance, and must renew your insurance unless you don’t pay your premiums. And even then, they must provide a grace period for you to catch up.

Also in Section 112, recision (rescinding your insurance when you get sick) is not allowed except for fraud, and per Section 162, the patient has a right to appeal. This goes into effect relatively soon, on October 1, 2010.

Section 113 is a big one: insurers must offer standard rates except some variation for age (no more than 2 to 1), geographic area, and family enrollment. Although I can’t make sense of the specifics of family enrollment—it’s on page 21 if anyone wants to figure it out. (Ha! I slay me.) This means:

- No charging insane premiums for people in poor health, and

- No surcharges when someone gets sick.

That’s a truly well-designed rule—it solves problems, it’s simple, and you don’t need armies of inspectors to enforce it.

However, there’s also a provision for a study to be done beforehand to make sure the rule isn’t too harsh on insurers. It seems to me this almost guarantees that the rule will be eroded to nothing by 2013—of course the insurance companies will say that it’s too onerous.

Section 116 states that if there’s too big a gap between the premiums paid in and the claims paid out (that is, if an insurer takes in twenty million dollars and only pays out five), the excess (to be defined later) is returned to the premium payers, not given out to shareholders.

That may seem technical, but done right it could be huge—it could take away insurers’ incentive to dick patients out of claims, at least past a certain point (because they wouldn’t keep the extra money they save). Instead, they’d have an incentive to keep administrative costs down (paying claims as a matter of course, instead of arguing every one, would be one way to do that) and offer better deals to get more patients on the plan.

Even better, according to section 161a this applies starting January 1, 2011 (like the rest of the bill should dammit).

Section 121-122 says plans must:

- Provide certain essential benefits (doctors, hospitals, outpatient treatments, drugs, rehabilitation, mental health, preventive services, maternity, well-baby care, and well-child care including oral health, vision, and hearing)

- Limit cost-sharing (like deductibles and copays) to $5,000 per individual and $10,000 per family (and can’t have any for preventive services)

- Not impose annual or lifetime limits on benefits

- Only deny benefits based on clinical appropriateness (and not, for instance, cost). Although nothing’s stopping them from arguing that whatever they don’t want to pay for is clinically inappropriate.

All of that’s pretty good, so let’s take a look at a stupid provision, section 164. It provides $10 billion to help group health insurers pay the cost of health benefits to retirees and their spouses and survivors. I can’t see any reason for this except that insurers want taxpayers to pay their obligations. And unlike every other provision in this bill, it goes into effect fast—a mere three months after the bill is enacted. Which shows how quickly insurers can adjust to government actions when they want to.

Anyway, those are the essentials. Here are some possible ways to improve this part of the bill:

- Define a minimum grace period for catching up on premiums (as it reads, the grace period could be seven minutes).

- The ban on recisions is good, but “except for fraud” is a big loophole. I imagine that many state laws forbid recisions except for fraud, but insurance companies still drop cancer patients for not mentioning that they had acne once. Why not make dropping patients (except for nonpayment of premiums) illegal altogether? That saves the expense and bureaucracy of an appeals procedure. After all:

- The act makes it illegal to exclude people.

- So if the insurance companies comply with the law, there’s no reason to commit fraud (like, conceal a pre-existing condition).

- So the only reason someone would commit fraud would be if the insurance companies were failing to comply with the law. In which case, the problem is the failure to comply, not the fraud.

- It’s not clear how the loss ratio (premiums/payouts) will be counted, which leaves open the possibility of financial chicanery (the same way that profitable corporations are broke when the tax man comes)—it’s worth putting in a provision that for public companies, the loss ratio declared to the government be the same as that declared to shareholders.

- We could save a quick $10 billion by letting insurers pay their own damn obligations to retirees.

- Not to be a broken record here, but rather than spending four years studying whether this rule or that is too difficult to comply with, put the system into effect and, if something really does prove to be too onerous, change it then. That’s another reason to have a robust public option—if the administrators of the public option think a rule is too hard to comply with, then change it. If other insurers piss and moan while the public option does fine, screw them.

Phew. On to:

In the exchange, insurers offer plans that the exchange then offers to anyone who’s not already in an acceptable plan (Section 202a).

- Plans must meet all of the requirements listed above. Also, anyone offering premium plans must also offer basic plans (both are defined at length in section 203, 204).

- People who are enrolled in the exchange can join any plan in the exchange (within a geographic area).

- Once you’re in an exchange plan you can stay in it even if you become eligible for another plan. You do lose your exchange coverage when you get on Medicare when you turn 65, or (I think) if you get on Medicaid after a bout of downward mobility (Section 202d4a, 202d4b).

- If you’re poor enough to be eligible for Medicaid, most of the time you’ll be enrolled in Medicaid and not the exchange.

- A state (or group of states) may choose to operate an exchange under the same general terms; such an exchange replaces the federal exchange in that state (Section 208).

Small employers will be able to opt into the exchange, at first ones with 10 or fewer employees, then 20 or fewer in 2014, and larger ones after that at the discretion of the commissioner. (Oh yeah, there’s a commissioner.) An employer remains eligible even if it later grows past the limit (Section 202c).

There are lots of technical provisions about administration, oversight, and things like risk pooling (if Plan A winds up with a bunch of high-risk people enrolled, while Plan B does not, some sort of adjustment will be made where part of Plan B’s premiums go to Plan A. I suppose that’s necessary to ensure adequate outreach to high-risk populations, but it sounds awkward and Jesus Christ can we just have single-payer already?). There may be some crucial weaknesses hidden in these provisions, but nothing raised any red flags for me.

The public option is pretty straightforward, to the point where there’s not much to say about it:

- It will be offered through the exchange (Section 221)

- It must meet the same requirements that the other plans in the exchange do (Section 221)

- It must pay for itself as they do (Section 221)

- It will pay mostly Medicare rates (Section 223)

Section 314 says that insurers can’t push their unprofitable members onto the exchange. I’m not sure why this is even specified—as it stands, insurers can’t dump unprofitable members at all. And if you’re going to specify something like this, you should also specify how it will be enforced, while the bill doesn’t do that.

And that’s pretty much it. In general, the public option is key here—every regulatory safeguard can be evaded or changed, but having to compete with a public option should keep other insurers on the straight and narrow.

There is, of course, room for improvement:

- The exchange doesn’t go into effect until 2013. Better to put it into effect and work out the bugs as we go along; by 2013 we’ll have a much better system.

- You can’t get into it unless you lack “acceptable” coverage, and your existing coverage is acceptable, by definition, until 2018 (and longer if it’s grandfathered). I suppose you could drop your existing coverage to get into the exchange, but not everyone can risk that.

- Why not let anyone enroll in the exchange? It would mean less bureaucracy and government meddling. As it stands, the government has the burden of judging a bewildering array of existing plans to decide whether they’re “acceptable” or not. If anyone could join the exchange:

- The public option would keep other plans in the exchange honest

- Other insurers would have to offer decent plans themselves or consumers would join the exchange.

- Anyway, why should the government decide whether my health care is acceptable? I should be deciding that, thank you very much.

And now, on to the money bits:

Employers are supposed to offer to cover most of the health insurance costs of their full-time employees (72.5% for individuals and 65% for families, Section 311, 312). The contribution is reduced in proportion to hours worked, so an employer can’t get out of the contribution by having two part-time workers instead of one full-time one. And taking the contribution out of the worker’s salary is also verboten.

Employers that don’t do that must pay 8% of payrolls to the exchange trust fund (Section 313). Small employers pay less—nothing at all for employers with payrolls of less than $250,000 a year, increasing in steps to 6% for employers with payrolls of less than $400,000 a year.

Also, people with unacceptable health care coverage will pay 2.5% of their income to the exchange, limited to the cost of an average premium. This will no doubt encourage people to get insurance (you’re paying either way), but penalizing people with no health care is also just a dick move, like when the bank makes you pay money for not having enough money.

And finally, there’s a new tax: It is:

- Nothing if you make $350,000 or less.

- 1% of your income from $350,000 to $500,000. And for all of the whining people will do, I’m sorry—if you’re making $500,000 and can’t spare $1,500, you are clearly too big a bozo to be earning that half-mil in any real sense, so taking it away from you is perfectly just.

- 1.5% of the amount from $500,000 to a million (so if you make $1,000,000 you pay $16,500. Again, deal with it).

- 5.4% of the amount over $1 million.

- That’s if you file a joint return. It’s less if you don’t.

This goes into effect in 2011, creating a cushion of money (and dishonestly making the ten-year costs of the program look better). The first two numbers double starting in 2013 (so someone making $1,000,000 will pay $33,000), but if the Medicare and Medicaid reforms produce decent savings, they don’t (p199). And if the reform produces lots of savings, the government will only collect the 5.4%. This money goes into general revenue (I think).

Sections 452 and 453 give the IRS more teeth to find tax cheats; this seems to apply in general, not just these specific taxes. So, good.

So much for the sticks. Now the carrots: subsidies for people who can’t afford health insurance.

The subsidies are based on family income—they make up much of the difference between the actual cost of an average plan and a specified percentage of your income.

- People at 133% or less of the federal poverty level only have to provide 1.5% of their income; the government covers the rest.

- The percentage rises in steps until someone at 400% of the federal poverty level will paying 11% of their income.

This is welcome recognition that the poverty level is outdated, and that people making many times that much still need help. 400% of the poverty level is $43,320 for an individual, or $88,200 for a family of four.

11% of $43,320 is $397 a month, which is still harsh, but it’s better than it looks—the government pays most of the difference not between that and the average premium (which might be no difference at all) but the real actual cost of a plan, including copays and deductibles.

The credits only apply to people in the exchange, and people with employer-provided health insurance are not eligible. But only real employer-provided insurance counts (where the employer pays most of your premium and doesn’t take it out of your paycheck).

And persons not lawfully present in the United States are unambiguously excluded in Section 242(a)1 and again in Section 246. It’s simply not possible to read this bill and believe that subsidy money will go to illegal aliens. So stick it, Joe Wilson.

There’s a tax credit for small businesses that provide health insurance for their employees.

Now: in his speech, Obama said that “[F]or those Americans who can’t get insurance today because they have preexisting medical conditions, we will immediately offer low-cost coverage that will protect you against financial ruin if you become seriously ill.” Honestly, I can’t see where that is in the bill. Anyone?

So how to improve this section?

- First of all, from a political point of view, putting a tax into effect before a big election year (2012), while waiting to provide the benefit until after the election, is a very good way to lose the election. Seriously, what the hell, Congress?

- The penalty for people who don’t participate solves a problem that may not even come up. Really, if the plan works—if insurers offer good plans and the government helps people out who can’t afford them—we can expect that most everyone will participate. If hordes of people stay out of the system, that means that either the plans suck or they’re not affordable. And if I’m wrong—if many selfish stupid people opt out of a perfectly good system to save on premiums and then demand care on the public dime when they fall ill—we can put the tax into effect then. No need to jump the gun.

- There’s no provision for the cutoffs for small business to increase with inflation. So a few years of bad inflation will be very hard on small businesses—they’ll have to pay taxes designed for larger businesses. Many other dollar amounts in the bill have provisions to increase with inflation (for instance, the legal cost-sharing amounts in section 122).

So much for financials. And you can really stop reading now—you’ve now received most of the wisdom I had to offer. But for the loyal or masochistic, I continue to:

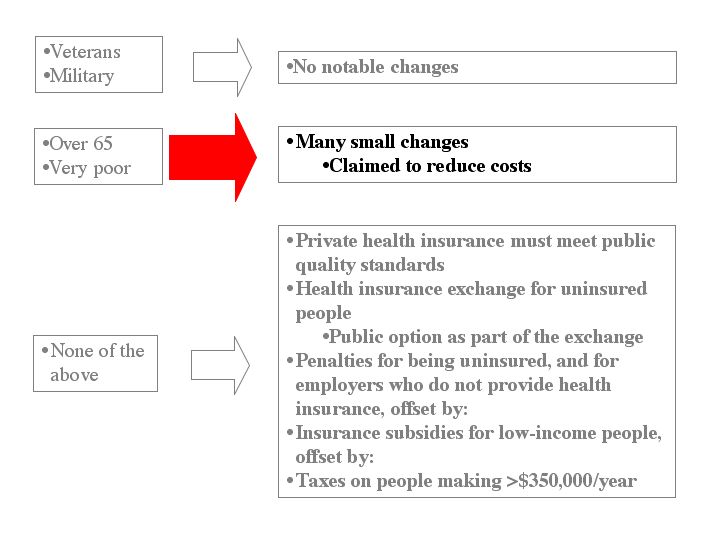

Honestly, this section baffles me—most of it is made up of changes in wording to previous law, which are meaningless in themselves (“Subclause IV is redesignated Subclause VI”) and which would take me another week to figure out. So I’ll limit myself to a few observations:

- This section is a big grab bag of changes with no clear focus. For instance, Section 1413, 28 pages long, improves a website where people can compare skilled nursing facilities.

- Section 1233 covers end-of-life planning. It’s entirely about making sure that the individual knows what options are out there, and that his or her wishes are respected. There is absolutely no possibility that an English speaker, even one as dim as Sarah Palin, could read this and honestly believe that it involves death panels.

- I don’t see where the big savings are expected. For every provision that looks like it should save money (cracking down on fraud, covering tobacco cessation drugs [Section 1712], keeping tighter rein on drug companies’ gifts to doctors [Section 1451], or making Medicare Advantage plans rebate excess premiums [Section 1173]) there seems to be another one that looks like it will cost money (e.g., closing the “doughnut hole” in drug coverage, Section 1181]). One possible exception is Section 1182, which involves substantial discounts on drugs, but it’s not clear to me under what circumstances that applies.

- In general, I just don’t think there are huge savings to be made.

- Depending on which numbers you look at, the average cost of health care per person in the U.S. is $6,000-8000 per year.

- Medicare pays out around $10,000 per year per person. In 2003, Before Bush’s giveaways to insurers and drug companies, that was $7,000 a year.

- Given that the over-65 set needs far health care than younger folks, Medicare is already pretty efficient (at least compared to the rest of our system). It seems to me that aside from repealing Bush’s giveaways (which is a good idea but doesn’t seem to be part of this bill), any meaningful savings would have to come from cutting flesh, not fat.

- Even the writers of the bill don’t seem confident that the expected savings will show up. As detailed above, if the savings don’t materialize, taxes on rich people go up instead. So, there’s that.

Anyway, that’s pretty much all I can say about this section.

There’s also a bunch of miscellaneous provisions, some of which look good (like strengthening our public health infrastructure) but I don’t have much to say about them either. I’ll close with two technical observations:

First of all, the bill was written so that, say, paragraph 142(C)5(d)3 is simply marked with a “3.” Given that each paragraph may go on for several pages, writing the whole number in front of each paragraph would make it much easier for the beleaguered reader to tell what’s going on.

Also, the government doesn’t seem to have any central, definitive, up-to-date online list of laws. So for instance, Section 442 of the health care bill moves the effective date of paragraphs 5, D, and 6 of 864F of the Internal Revenue Code to 2019 instead of 2010. But I have no idea what that means, because the best online version of the Internal Revenue Code (at Cornell) seems to be out of date; the changes don’t make sense with the paragraph 864F as written there. In this day and age it wouldn’t be too hard to maintain a website with the current text of all our laws on it.

Aaaaand I’m done. If you made it to the end, get yourself some ice cream. You deserve it.

|

|