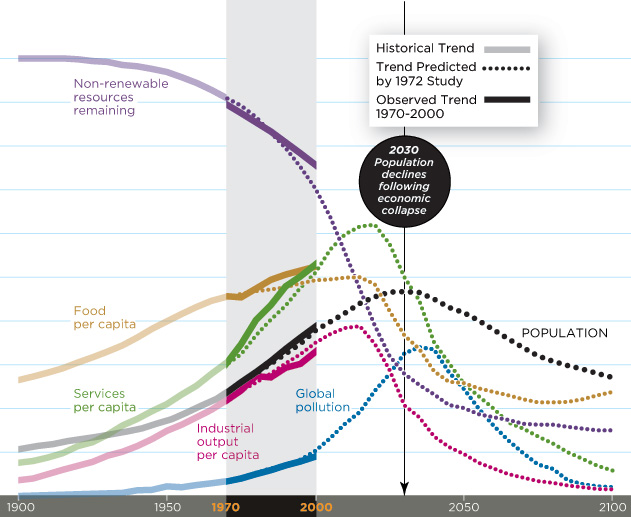

By Mike Here’s a chart showing the Club of Rome’s 1972 predictions for the future, as given in Limits to Growth, and how things have worked out since then. Pretty accurately. Frighteningly accurately.

I’ll take the liberty of reprinting it, for those who don’t want to click on the link. It’s copyright etc. the Smithsonian magazine.

The Club of Rome was, notably, not Paul Ehrlich, who wrote The Population Bomb at around the same time. Ehrlich said that the world was already in a crisis of scarcity brought on by population growth. He famously lost a bet to one Julian Simon, who believed the opposite–that more humans meant more chickens, not fewer, and that we would see abundance in the future, not scarcity. (Ehrlich bet on the prices of commodities going up, Simon bet they would go down; by the 1980s, they had gone down.)

Ehrlich’s lost bet became famous, and was used to discredit everyone who said, hey, maybe resources aren’t unlimited.

Which is a shame (using the definition of “a shame” that means “something that may very well kill most of us”). Unlike Ehrlich, the Club of Rome argued that, although growth could continue for some time longer, we would hit limits in the near-to-medium future. They predicted, among other things, an economic collapse followed by population decline in 2030.

As of 2000, as the link above shows, we were not exactly on schedule, but close.

I’m not sure why the chart in the link isn’t brought forward to 2010; the data must exist now.

EDIT: The data are old, it turns out, because the analysis is several years old. I violated my own principle of always going back to primary sources before giving an opinion.

Also, the Club of Rome gave several predictions based on different assumptions. The scenario that’s played out so far has been the “business as usual” scenario. As opposed to, say, the “everybody becomes sane and actually starts to deal with these problems” scenario, which must have seemed at least achievable in the 1970s.

Finally, this is testable: If the model is correct, we should be looking at a decline in industrial output within a few years, followed by a decline in global food per capita soon after.

By Mike From Dwight D. Eisenhower:

“If all Americans want is security, they can go to prison.”

Quoted in William Manchester, The Glory and the Dream, page 745

He said that in the 1950s; he no doubt didn’t mean it to be a prediction.

By Mike So apparently, the Supreme Court case on Obama’s healthcare reform is rapidly descending into madness.

Let’s start with the objection to mandates. Paul Krugman gives the counterarguments here. To quote:

Is requiring that people pay a tax that finances health coverage OK, while requiring that they purchase insurance is unconstitutional? It’s hard to see why — and it’s not just those of us without legal training who find the distinction strange. Here’s what Charles Fried — who was Ronald Reagan’s solicitor general — said in a recent interview with The Washington Post: “I’ve never understood why regulating by making people go buy something is somehow more intrusive than regulating by making them pay taxes and then giving it to them.”

I would only add that while the government can directly compel us to buy things, it generally doesn’t, for a very good reason: It’s irritating. And that irritation–our dislike of being told what to buy, an intrusion that is softened if we simply pay taxes and get the thing instead–is the control on government power here. That is, we’ll only put up with such obvious intrusion in certain special cases.

In fact, one might expect conservatives to argue that every government program should be mandated like this, in order to make the government intrusion clearer and more irritating. And in fact, the idea for mandates came from the neanderthal-right Heritage Foundation. And replacing Social Security with private accounts? The darling idea of conservatives everywhere? Yup, that would involve mandates.

So the argument against mandates comes down, not to any principle it violates, but to the fact that it’s Obama who wants them.

But that’s not the craziest part.

The Supreme Court–or those appointed by presidents named Bush or Reagan–seems to be actually listening, seriously, to another argument. Marty Lederman on Balkinization explains it clearly. To paraphrase:

- Way back when, Congress made Medicaid money available to the states, with conditions on how it be spent (i.e., they had to spend it on something resembling Medicaid, not on hookers and blow).

- States could refuse the terms by refusing the money. This is not federal coercion in any possible sense of the word.

- The current law will, in 2014, provide more money, with new conditions for that money.

- The money is provided all together–states can turn it all down, but not just the new money.

- The states with Republican attorneys general are saying that this is unacceptable coercion–they want (or say they want) to turn down the new money without losing the existing money.

But what if Congress had simply:

- Cut off Medicaid funding in 2014,

- Immediately instituted a new program, with more funding, that covered the same bases and more,

- Allowed states to opt out of the new program if they chose (I say “allowed” just to stress the point–in fact states have a clear and unchallenged right to opt out)

- Called the new program Medicaid in order to save on letterhead?

That would be exactly the same thing.

Given that steps 2, 3, and 4 are clearly constitutional, the state AGs are arguing that step 1 is unconstitutional coercion.

Which means saying, essentially, that Congress cannot ever stop funding something once the states have gotten used to the money.

This is so far from sane law, common sense, and even conservative ideology that I’m wondering whether the state AGs deliberately made pathetically weak arguments. That would make sense: any state AG who said, “hey, this program means a lot of money for our state and we shouldn’t fight it” would have no career in the Republican party, but that doesn’t mean that, as individuals, they actually want to fuck over their own states. They may have figured that the Supreme Court would reject their arguments. Their careers are intact, their states get that sweet federal money, everyone wins.

But if that was the plan, the joke is on them: many justices are treating their funhouse arguments as grave and sensible.

And why should we be surprised? This is the court that decided, in Bush v Gore, that George W. Bush should be president and fuck you. Of the five justices who gave us that travesty, three are still on the court. The two who left were replaced with worse ones.

The sad thing is, it’s 2012. The health care bill passed two freaking years ago, but the best parts–the parts that actually insure most of the uninsured–still haven’t gone into effect and won’t until 2014. And some will take longer than that. If they had gone into effect–if more people saw the benefits in their own lives–fighting it would be political poison. (The state AGs aren’t fighting the existing program, because the existing money is popular. It’s the program that we haven’t seen that they can fight, for the exact reason that we haven’t seen it.) The right wing has had years of opportunities to kill decent healthcare before it’s born because it has taken such a ridiculous time to *be* born.

I can’t help but quote my own post from 2009:

It’s not that fixing a health insurance plan really takes that long—nine years (2009-2018) was enough time to create a military from scratch, fight World War II, dismantle the military, and rebuild it for the Korean War. Back in the thirties, nine years was enough time to create important programs like the Works Progress Administration, the Public Works Administration, and the Civilian Conservation Corps, have them do their work, and dismantle them.

On the other hand, the long delay gives the forces against reform time to undermine it, and an entire freaking presidential election campaign to replace pro-reform politicians with ones more amenable to their interests. One doesn’t have to be paranoid to think that maybe this is the point.

I didn’t think of the legal aspect at the time. More fool me.

By Mike Jim Hightower on Common Dreams has an eloquent defense of the Post Office, including the fact that it’s not actually broken at all–the reason it’s having a budget shortfall is that Congress basically tried to kill it.From the article:

The privatizers squawk that USPS has gone some $13 billion in the hole during the past four years — a private corporation would go broke with that record! (Actually, private corporations tend to go to Washington rather than go broke, getting taxpayer bailouts to cover their losses.) The Postal Service is NOT broke. Indeed, in those four years of loudly deplored “losses,” the service actually produced a $700 million operational profit (despite the worst economy since the Great Depression).

What’s going on here? Right-wing sabotage of USPS financing, that’s what.

In 2006, the Bush White House and Congress whacked the post office with the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act — an incredible piece of ugliness requiring the agency to PRE-PAY the health care benefits not only of current employees, but also of all employees who’ll retire during the next 75 years. Yes, that includes employees who’re not yet born!

No other agency and no corporation has to do this. Worse, this ridiculous law demands that USPS fully fund this seven-decade burden by 2016. Imagine the shrieks of outrage if Congress tried to slap FedEx or other private firms with such an onerous requirement.

This politically motivated mandate is costing the Postal Service $5.5 billion a year — money taken right out of postage revenue that could be going to services. That’s the real source of the “financial crisis” squeezing America’s post offices.

I would only add a couple of things:

- I pay ten cents to send a freaking text message. The recipient, depending on the plan, might also pay ten cents. So, the “magic of the market” charges more to send three text messages than stodgy old government does to carry an actual physical letter across the country.

- We love to complain about the Post Office, but in my experience it’s more reliable than Fedex. That guy who threw the (clearly marked) TV over the fence, rather than open the gate or ring the bell? He didn’t work for the government–he worked for dynamic private industry.

- In my experience, the Post Office is *far* more reliable than UPS, which has the “hey, we lost your package and we don’t give a shit and there’s nothing you can do” attitude that, if the econ texts were correct, would only be seen in socialism.

- I don’t think conservatives in Congress want to kill the Post Office because it’s failing. Failing public programs don’t challenge their worldview. I think they want to kill it (and are killing it) because it’s succeeding–because it’s a daily reminder that their entire ideology doesn’t pass the smell test.

So I guess I disagree with this, from the article:

The corporatizer crowd doesn’t grasp that going after this particular government program is messing with the human connection and genuine affection that it engenders.

I think they understand that very well indeed.

By Mike Our quote of the day comes from William Jennings Bryan:

“They call that man a statesman whose ear is tuned to catch the slightest pulsations of a pocketbook, and denounce as a demagogue any one who dares to listen to the heartbeat of humanity.”

Quoted in Jason Goodwin, Greenback, page 275 of the hardcover edition.

By Mike This is good news: Obama just nominated Jim Yong Kim for head of the world bank.

Who is Jim Yong Kim? Apparently he’s a physician and an expert on health, which might be good to have at the head of an institution whose mission is to actually do good instead of just make a profit.

But he could be a bag of rocks and I’d be happy, because he’s not Larry Summers, who was rumored to be one of the top candidates. The same Larry Summers whose policies boiled down to taking care of Wall Street. The guy who’s a large part of the reason we’re in the mess we’re in today.

For that matter, he’s not Jeffrey Sachs, another frontrunner. There’s more to like about Sachs than about Summers, but Sachs was a big advocate for “shock therapy” after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The shock therapy that turned out to be all shock and no therapy, that devastated Russia’s economy and wound up ending its democracy.

This is maybe the first time that one of Obama’s big economic appointments went outside the circle of usual suspects. Maybe he’s starting to question his own decision to listen to the Summerses, Sachses, Bernankes, and Geithners of the world. Which is all to the good. After all, they had their chance. They blew it. They should get off the stage and give someone else–anyone else–a shot. I wish Obama had realized that three years ago, but if he’s realizing it now, heck, that’s better than nothing.

By Mike Our quote of the day comes from Martin Peretz, editor-in-chief of the New Republic, in 1989.

“The cheer with which Western commentators greeted Mikhail Gorbachev’s tease that the Berlin Wall might come down when the conditions that generate the need for it disappear is another sign of how credulous we have become in receiving blandishments from Moscow.”

It’s available here.

Thank god we had people like Peretz looking out for us.

By Mike I mentioned our screwy patent system last post; today comes the news that the Supreme Court has decided that, essentially, natural laws can’t be patented.

From the article:

In general, Justice Breyer wrote, an inventor must do more than “recite a law of nature and then add the instruction ‘apply the law.’ ”

“Einstein, we assume, could not have patented his famous law by claiming a process consisting of simply telling linear accelerator operators to refer to the law to determine how much energy an amount of mass has produced (or vice versa),” he wrote.

So, that’s actually good. But it’s still evidence that our patent system is broken.

Point being, given that it’s possible to patent things that are in no way inventions, like genes and one-click shopping, it made sense for companies to try to patent natural laws, and to bring their claim all the way up to the Supreme Courth. Yes, the Court said no in this case, but in a reasonable patent regime this wouldn’t have even been a question.

By Mike Consumerist.com reports that Microsoft has patented a system that would let people pay to skip commercials.

That could be the start of a rant about our broken patent system (is this really something that needs a patent? Isn’t it sort of obvious?), but I’m on a different rant today.

Specifically:

- People will pay to avoid advertising. If we wouldn’t, there would be no point in this patent.

- Things we pay to avoid–or would if we could–are, by definition, bad.

- Therefore, advertising is, in and of itself, bad. Not just its effects, which are bad enough, but the simple fact of its existence, which causes us some amount of annoyance that we would pay to avoid.

Now: in many cases advertising is a tradeoff–I want to watch Jersey Shore, so I’ll sit through some ads in order to do it; the irritation of the ads is worth it for that Jersey Shore goodness.

But what about ads that don’t support anything–that just accost us? Like billboards? Or spam phone calls?

Why are they legal? Spam calls to cell phones are in fact not legal, but why are any spam calls allowed?

And check this out: Sao Paolo, in Brazil, got rid of billboards. Here’s what a business owner there had to say about the effect that had:

“You have to change the whole structure of the business. Today we work instead of investing in advertising, to have something that attracts the customer. Our job is to look for referrals.”

(Quoted in The Greatest Movie Ever Sold.)

In other words, restricting advertising means that businesses have to compete the way that textbooks say they should–by actually attracting customers with their products, their services, or their prices.

Okay, that wasn’t even other words–that was many of the same words.

Point being: If we will pay to skip ads in videos and whatnot–and Microsoft is betting that we will–we would no doubt, if we had the option, pay to skip ads on billboards, on our phones, in bar bathrooms, and suchlike.

Thus, getting rid of these things would make us better off. In theory at least, measurably better off (by the amount of the money we would have spent to avoid the ads).

I can’t find any research about how much people would pay to avoid all the crap that the ad industry dumps on us, all day, every day. But certainly it’s more than zero, while the social benefits of all these ads are less than zero.

So why allow them?

By Mike Well, this is bad. An article on Truthout details how a new Pennsylvania law makes it difficult for us to even know what chemicals frackers are using, much less what they’re doing to us, because they’re trade secrets. Check out how difficult it is to get, and especially to share, information that may be needed for medical reasons. From the bill itself:

A vendor, service company or operator shall identify the specific identity and amount of any chemicals claimed to be a trade secret or confidential proprietary information to any health professional who requests the information in writing if the health professional executes a confidentiality agreement and provides a written statement of need for the information indicating all of the following:

(i) The information is needed for the purpose of diagnosis or treatment of an individual.

(ii) The individual being diagnosed or treated may have been exposed to a hazardous chemical.

(iii) Knowledge of information will assist in the diagnosis or treatment of an individual.

If a health professional determines that a medical emergency exists and the specific identity and amount of any chemicals claimed to be a trade secret or confidential proprietary information are necessary for emergency treatment, the vendor, service provider or operator shall immediately disclose the information to the health professional upon a verbal acknowledgment by the health professional that the information may not be used for purposes other than the health needs asserted and that the health professional shall maintain the information as confidential. The vendor, service provider or operator may request, and the health professional shall provide upon request, a written statement of need and a confidentiality agreement from the health professional as soon as circumstances permit, in conformance with regulations promulgated under this chapter.

There’s really no way to interpret this except:

- If you’re a health care professional, you can get a list of the chemicals a patient has been exposed to, if the patient is already sick, if you’re alert enough to suspect that he or she has been exposed, and if you’re willing to jump through hoops.

- You can use that information to diagnose and treat your patient, but not to, for instance, warn other physicians, or the public, to be on the lookout for signs of exposure to this chemical, because hey, that’s a trade secret.

The focus on the “proper diagnosis and treatment of an individual” is worrisome too–the thing is, any cancer, any bizarre health problem, can happen once in a while. If the rate of a rare cancer doubles, individual physicians, treating individual patients, might not notice anything is wrong if it’s the difference between seeing one patient with it and seeing two. It seems to me like a public health professional, seeing a cluster of cancers, wouldn’t be able to get information about what those people were exposed to without getting one of their individual doctors to request it.

Worse, the public health professional wouldn’t be able to look proactively–for instance, to see what happens in communities that have been exposed to chemical X–because she wouldn’t be able to tell which communities had been exposed to which agents until people start getting sick.

I’m sure that this was put through by people who preach free markets, but it resembles a true free market–which requires people to be informed about the consequences of the choices that they make–not at all. In a true free market, people might say, hey, we want cheaper gas and we’re willing to take this known risk to our health in order to get it. Which is not to say that’s the ideal, but that’s how a free market is supposed to work.

And when the coercive power of the state is used to maintain our ability to make informed decisions (like with mandatory food labeling), the result is a market that works better.

But using state power to prevent us from even knowing the risks we’re taking, so we have no practical choice but to buy what people want to sell us, resembles nothing so much as mercantilism. Not a free market, and certainly not democracy. I just can’t stop quoting Adam Smith:

It is unnecessary, I imagine, to observe, how contrary such regulations are to the boasted liberty of the subject, of which we affect to be so very jealous; but which, in this case, is so plainly sacrificed to the futile interests of our merchants and manufacturers.

And for that matter:

It is the industry which is carried on for the benefit of the rich and powerful, that is principally encouraged by our mercantile system. That which is carried out for the benefit of the poor and the indigent, is too often, either neglected or oppressed.

|

|