By Mike We hear a lot about the “stimulus vs austerity” debate. The phrase (in quotes) gives more than half a million hits on Google. But that’s a crude, inaccurate way to think about our policies.

The fact is, we have both stimulus and austerity now. The stimulus is for the rich (the “job creators” who need endless tax cuts) and for big corporations. The austerity is for the rest of us (“hey, sorry, there’s no money to fund your school, because we had to help out the job creators”).

But it wasn’t always this way.

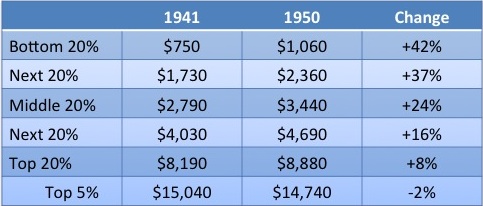

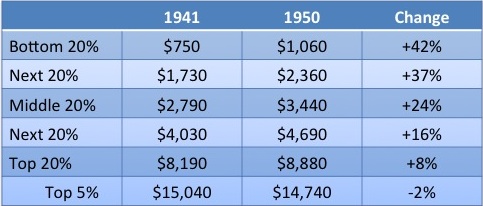

Check this out: This is how after-tax incomes changed from 1941 to 1950, by income bracket:

That’s a 42% increase in spendable income for the bottom 20%, compared to only a 8% increase for the top 20%. And the top 5% actually lost spendable income, even as the economy zoomed (first for the war, and then, after a break, as the peacetime expansion got going).

So back then, we had the opposite of today’s policies: Stimulus for the poor (lots of spending and low taxes), and austerity for the rich (high wartime taxes that were kept in place after the war).

And that should be our debate: not whether we need stimulus or austerity, but whether we need to switch the targets of the stimulus and the austerity.

I say “debate,” but the answer is really as obvious as anything in the economy can be. The current system stinks. The old system worked. We should go back to it.

And no, taxing the rich won’t magically kill the economy; high taxes on the rich actually correlate with good economic performance.

(Source for the table: Goldsmith S, Jaszi G, Katz H, Liebenberg M. Size distribution of incomes since the mid-thirties. Review of Economics and Statistics. 1954 Feb; vol 36. Quoted in Galbraith JK, The Affluent Society, Riverdale Press, 1958: p86.)

By Mike Someone pointed me to the photo collection Mugshots of the 1920s, from the files of the New South Wales police.

All the pictures are worth a look, but I took a special interest in this guy:

Not that the photo itself is better than the rest, but here’s the police description:

A con man who sells suburban building blocks at grossly inflated prices, by falsely leading the buyers to believe the lots may be promptly resold for a huge profit.

Hence the title of this post. We could put real estate con artists away a century ago, we can do it today.

By Mike Dylan Matthews, at the Washington Post’s Wonkblog, has a pretty well-reasoned piece suggesting that we should just get rid of the laws against insider trading.

That sounds crazy at first, but it’s hard to argue with most of his reasons–in fact, I’m on record saying some of the same things, including:

- Insider trading laws are designed to make us civilians trust the financial system. Matthews says, reasonably, that we shouldn’t trust the financial system–we should understand that it’s a place where insiders, simply by being insiders, get to fleece everyone else, and we shouldn’t even bring them our money.

- Even if insider trading laws were ruthlessly enforced, it would be impossible to prevent “insider nontrading”–simply not taking bets that you otherwise would have taken.

Matthews does make a few points I find less compelling, like the idea that we want people to put their money in index funds. I think that would worsen other problems on Wall Street (when a million people own a stock, nobody has much power over the company; when a million people combine their stock into a fund, the manager of that fund has quite a bit of power and can demand that the company declare a special dividend or buy back stock or do any of the million things that Wall Street—and only Wall Street—thinks are good ideas).

But on the other hand, there’s another reason to legalize insider trading that Matthews doesn’t mention: It would pretty much end the mystique of financiers.

Imagine if everyone understood that Wall Streeters made more than the rest of us, not because they made smarter trades with the same information, but because they just plain knew what was going to happen in a way that the rest of us never could?

Who would argue that they deserve their ridiculous pay, when they were clearly doing what any bozo could do in the same position? Who would say that we need to keep taxes on them low?

So yes, maybe it is time to legalize insider trading–we could stop pretending that Wall Streeters are smarter than the rest of us, or that they’re doing us any favors by making money for themselves.

By Mike I of course obsessively Google my own name, and I just found that the Hipcrime blog mentioned my talk at the Full Circle Series (recording available at the C-realm site here). More than that, they actually bothered to transcribe part of it! It reads much like I was giving a talk without notes (which I was), but I’m surprised at much sense I made. Here’s Hipcrime’s transcription:

It turns out that here is a whole forgotten tradition of economics, a very liberal and almost radical tradition of economics that has really; as I said, it’s forgotten. It’s amazing the degree to which it’s fallen off the radar. The most prominent practitioner of this, was a guy named John Kenneth Galbraith. He was a big-shot academic, but he also wrote popular books, and his first big best–seller was called The Affluent Society. And If anybody remembers that book at all, people say that Galbraith was being arch or sarcastic when he was talking about “the Affluent Society,” and that he was talking about really, how poor we were, or whatever. That’s not true. The book The Affluent Society was exactly about that.

His point was, and he was his writing in the fifties, his point was, we’ve solved the problem of production. We can make anything we want; any thing we want, in more or less the quantities we want it. Anything that comes from private industry, whether it’s a car or a razor or whatever, it’s coming in enough profusion that we don’t really have to worry about that aspect of the economy anymore. And his evidence was, look around you. Look at all these people trying to convince you to buy stuff. Hungry people don’t need to be convinced to buy food. Naked people don’t need to be convinced to buy clothes. The most advertising that anyone would do in that situation is just to tell you where to find it. But that’s not the sort of advertising he was seeing in the fifties. That was the fifties; it’s gotten much worse since then. If we were still at the other space; at the other space there were ads in the elevator, because God forbid you should spend that ten-second ride without possibly being convinced to buy something.

And so, all this advertising is expensive, and they wouldn’t do it if we actually wanted the things they were making. Which is actually a pretty radical thing to say, because all our economic ideas are based on the idea that at the end, when people make stuff and sell it, they’re filling our wants. That I may want a silk shirt one day, and a cool new razor the next day, and if I do, that’s great because somebody’s actually coming and supplying that want, and the amount of misery in the world goes down a little bit. But if we didn’t want the thing until these people actually made it and convinced us to want it, then the whole system is not quite as good as we thought.

Far more radical was his next book called The New Industrial State. That’s where he asked the question, ‘well, who’s doing this?’ And obviously you or I can’t afford gigantic marketing campaigns. His point, which is pretty obvious, is that these giant marketing campaigns are coming from very big businesses. But then he made the point that not only do these big businesses like to convince us to buy things, but they actually need to. They have no choice. And he took the example of a car: You start designing a car, you have to tool up, you have to hire the workers, you have to find a plant, all this stuff. And mainstream economics would have it that, after all this process, the car company goes to the free market and lets supply and demand dictate how much they’re going to sell and at what price. And his point is, they can’t possibly do that! They have to control the whole process, including sales. When they start designing the car, they have to know more or less how much it’s going to cost, and they have to be pretty well sure that they’re going to sell enough. And they ensure they’re going to sell enough by advertising.

So GM manufactures cars, and then GM manufactures our desire for cars, and everybody’s happy unless you think we don’t need quite so many cars. Now note how radical this is. Again, you’re getting very far away from the image that we have of businesses as just these helpful things that are giving us things we want.

Galbraith was very big until the nineteen-seventies. And to really take him seriously means abandoning all of economics and a lot of our social thought and completely rethinking our economy, and that’s very hard. And things seemed to be going okay, so he really got dropped and forgotten. And one reason is, we don’t like to be told we’re being manipulated. We like to think that we’re making our own decisions.

The Hipcrime post also has other transcriptions of parts of other podcasts that are worth reading. Check it out!

By Mike The New York Times has a well-researched article on how banks have been entering commodity markets (like aluminum); it makes the case that Goldman has been profiting by restricting the supply of aluminum, while consumers have paid extra, to the tune of like $5 billion. Not all of that $5 billion has gone into Goldman’s pocket–other aluminum sellers have benefited as well–but still, this article is damning, and in a sane world the Justice Department would be screwing Goldman to the wall for anticompetitive practices; this is a “conspiracy in restraint of trade” if I ever saw one.

And it’s not even the worst part.

The article also mentions that Goldman can use its insider knowledge of the aluminum markets in its derivatives operations (derivatives are essentially bets). So Goldman can, knowing that aluminum stocks are low, bet that the price will go up. Goldman makes money on what is more or less a sure thing. This sort of insider trading is illegal in the stock market, but in the derivatives market anything goes.

And that’s not even the worst part.

Here’s the worst part, and what the article doesn’t mention: Since Goldman influences the price of aluminum, it can explicitly manipulate the aluminum market so that its bets in the derivative market pay off.

And if it can, you can bet that it is.

That may seem paranoid, but that assumption is the only rational one to make since the LIBOR scandal.

For those who need a refresher, here’s the LIBOR scandal in brief: many big, old, respected banks reported an interest rate called the LIBOR, which was the basis of all sorts of other contracts–like how Americans’ credit card interest or mortgage is tied to the prime rate. It turned out that these banks were manipulating the LIBOR. The thing was, the manipulation wasn’t just of the “oh, shit, we’re in trouble, let’s lie about how much trouble we’re in” kind (although that happened). That would be kind of understandable. But banks also manipulated the LIBOR constantly, routinely, to make sure that the bets that they’d made on the LIBOR paid off. So, you’d take a bet that the LIBOR would go down in three months, and then three months later you’d lower the LIBOR.

And the gains in question were often tiny–barely a blip on these banks’ balance sheets.

That’s like the difference between finding that some judges occasionally take bribes for $100,000 or more, and finding that judges routinely change verdicts for five bucks and a 40-oz bottle of Colt 45. The one is bad, but the other means that the entire system is so deeply fucked up that the very assumptions behind it (like the assumption that most judges can be trusted most of the time) have to go.

The thing is, the LIBOR was easy to manipulate because it was set more or less by the honor system–banks self-reported the interest they were paying. And that’s the point. Banks’ honor was at stake, and they themselves valued it at nothing. And so must we.

Now: Even before the LIBOR scandal I thought it was obvious, in the words of one of my own posts, that financiers are dangerous idiots who need to be watched every minute. But after LIBOR there’s no way that anyone with a brain should think anything except: If banks have the opportunity to cheat, they’re going to cheat. Period.

Goldman has the opportunity to manipulate commodity prices to make sure its own bets pay off. It will. It is. Period.

So: What’s the solution? Well, as so often happens, this problem was the result of deregulation–banks were once forbidden to enter the commodities market–and the obvious solution is re-regulation.

Banks somehow managed to do business when they weren’t allowed to fuck around with commodities. They would find a way to do so again. Hey, maybe by, you know, making loans at interest to businesses and individuals. Nah, that’s crazy.

By Mike Les Échos is a French financial newspaper dedicated to the proposition that markets are better than planning (as a rule of thumb). And they like Economix! This might be the closest I’ve come to an official notice from the financial world.

By Mike So, it’s summer. It’s hot and it’s going to get hotter. You may be thinking of buying an air conditioner.

Before you do, though, why not buy new lightbulbs–those swirly compact fluorescents–instead?

Sure, you answer. Or hey, why not a new camera lens? Or a hundred pounds of bacon? Or a pony?

Bear with me. This actually makes sense.

If you’ve ever considered replacing your incandescent lightbulbs with CFLs, your thought process probably went something like this: “CFLs are more expensive, but they save on electricity and they last longer. Is the up-front cost worth the long-term savings?”

Whether your answer was yes or no, though, that was the wrong way to think about it.

See, a 60-watt incandescent lightbulb that puts out no more light than a 15-watt compact fluorescent isn’t just costing you 45 watts. That wasted energy becomes heat. Heat that goes into your home. Heat that you then take out with an air conditioner.

Now: According to this, those 45 watts will add 153 British thermal units (BTU) of heat in an hour. Conveniently, air conditioners are rated in BTU per hour. So let’s say you change five bulbs. That’s around 750 BTU that you don’t have to remove.

And remember, ACs don’t usually run continuously; a 6,000 BTU unit that runs a third of the time is only removing 2,000 BTUs per hour.

So if you switch your bulbs, you may find that you can get a smaller (and cheaper) air conditioner. You may not even need one at all.

And if the savings on the air conditioner is more than the cost of the bulbs, there’s no up-front cost at all. Going green means savings now *and* lower electric bills (much lower, thanks to the lower AC costs) later.

Note that the waste heat isn’t an argument for using incandescents in the winter; they’re not efficient heaters.

Now: This all depends on a million factors: when you light your home, where your bulbs are, how insulated your home is, and so on. But electrical bulbs certainly can make a difference. I know because they did for me; I got an air conditioner a decade or so ago, used it for two summers, and then stopped even bothering to take it out of the closet. Eventually I gave it away. I never understood why I’d stopped using it–the summers were no cooler, and I was no more tolerant of heat–until I remembered that that was when I’d switched to compact fluorescents.

So before you buy an air conditioner, switch your bulbs. You may save on both ends.

By the way: this phenomenon, where taking a larger view gets us out of the mindset of tradeoffs between up-front costs and long-term savings, is actually pretty common when you’re dealing with environmental issues. Lovins, Lovins, and Hawken’s Natural Capitalism is full of examples. For instance, if you’re building an office building and deciding whether to pay extra for well-insulated windows, that’s a tradeoff if you just compare the cost of the windows to your future heating and cooling bills. But less heating and cooling means that you can install smaller equipment and smaller ductwork, thus making a smaller building overall with the same useable floor space (and the smaller building means even less heating and cooling). If you save more making a smaller building than you spend on the windows, there’s no tradeoff.

So why don’t we think that way more often? I think that one reason is that economists *always* think in terms of tradeoffs, because in economic theory if there’s a win-win move to be made, we’ve already made it. As economists say, people don’t leave hundred-dollar bills lying on the street. Which isn’t wrong as a rule of thumb, but economists like to make rules of thumb into eternal principles. So if we assume that the savings aren’t there, we don’t look for them, and we wind up living in a world of $100 bills, only slightly hidden, that we don’t pick up.

By Mike So, the French version of Economix has been getting some awesome reviews. Here’s Phillipe Arnaud in Le Monde, which even I, in my America-based provincialism, had heard of:

“Proof that one can make difficult concepts intelligible without the encumbrance of mathematics!” (My translation.)

And Omri Ezrati at Al Bayane (a Francophone Moroccan outlet) says:

“Combining comics with clear text and plenty of humor, this graphic novel transforms the “dismal science” of the economy into an amusing history accessible to everyone. . . . Economix is indispensable in all libraries.”

I of course check my Amazon rankings every couple of minutes; now I’m checking my ranking on Amazon France as well. It’s up there!

By Mike Friday, June 21, 12:10 PM: A day that will live forever. For it is the day that I, Mike Goodwin, will be speaking at Port Washington Public Library. Come by! I’m working on my talk now–it should be good.

Info is here: http://www.pwpl.org/blog/2013/05/11/sandwiched-in-101/

By Mike Bruce Bartlett, in the awesomely named but unrelated Economix blog over at the Times, has a piece that makes a point that I’ve been thinking for years: Finance is a drag on the economy.

This goes against all sorts of economic orthodoxy; in this view, if we’re paying banks, stockbrokers, and real estate agents more than we used to, it *must* be because they’re providing us more services we want. They must be finding us more appropriate housing, giving us better insurance products, and investing our savings more alertly. Otherwise, we wouldn’t pay them so much, would we? Thus, if FIRE (finance, insurance, and real estate) has risen from 4% to 8% of GDP, that’s pure gain, just as it would be if, say, computer sales rose in the same proportion. More financial services for all! Isn’t that great?

Well, no. This is one of those assumptions that starts to dissolve as soon as you state it clearly. Nobody *wants* investment analysis, or real estate advice. We want homes, and incomes from our savings, and loans for our businesses, but we don’t want the services that bring them to us any more than we want the trucks that bring us our Cheetos; the trucking is a cost of getting what we want (and, unlike finance, is treated as such in GDP). If the cost of transportation doubled–especially if that happened because a few giant trucking companies just started raising their prices and fuck you, which is exactly what’s happened with banks–that wouldn’t be seen as a good thing.

Another way to look at it–we’re very used to thinking of health care as a drag on the economy. I don’t agree with that, but it does raise the question: In what possible universe is health care a drag and finance not?

Anyway, Bartlett’s column is worth reading. I don’t always agree with the guy, but when he’s right he’s right.

|

|