Behold! It’s available here.

Key word: “brilliantly.”

In other news, the fact that I can’t italicize titles in post headers drives me far more crazy than it should. . . .

|

Behold! It’s available here. Key word: “brilliantly.” In other news, the fact that I can’t italicize titles in post headers drives me far more crazy than it should. . . .

Mark Miller at Reuters has an article, “The Top Six Myths About Medicare.” It’s a model of clear thought and clear writing. You should read it. That is all.

There’s a sort of constant, low-grade handwringing about the fact that the Chinese economy—which overtook Japan as the world’s second-largest economy a couple of years ago—is expected to surpass the US in maybe 2016. But really, that’s already happened. China is now, today, the world’s biggest economy. And has been for a while. The long dominance of the US is over. Why is everyone else wrong? That is, ahem, a question I ask myself a lot. In this case, the answer comes down to how to compare two economies. The most straightforward way is to simply compare GDPs. That’s nice and mathematical, but that gets screwy because of exchange rates. For instance, in America a barber might charge $10 for a basic haircut. Every time an American barber gives a haircut, the U.S. GDP goes up by $10. In China, the barber might charge 7 yuan (I’m making this up), so every time a Chinese barber gives a haircut, the Chinese GDP goes up by 7 yuan. Now: if a dollar trades for 7 yuan, then a haircut in China only raises China’s GDP by a dollar. But a haircut is a haircut—the US haircut doesn’t somehow cut ten times more hair than the Chinese. And if a cheap meal also costs 7 yuan in China and $10 in the US, then both barbers can give a haircut for enough money to get a cheap meal. We can, of course, adjust the numbers to achieve “purchasing power parity.” So if you multiplied all Chinese prices by 10, the haircut and cheap meal in China would count as $10, same as in the U.S. That comes closer to reflecting reality, but there’s no one number that you can adjust all prices by. For instance, a decent bottle of wine might cost 70 yuan in China. At 7 to 1, that’s $10. Multiply all Chinese prices by 10, and the haircut comes out right but the wine counts as a ridiculous $100. Still, GDP adjusted for purchasing power parity is generally treated as the best number we have. That 2016 date is based on it. But what about energy use? Energy in the sense of fossil fuels, hydropower, wind, everything except human and animal muscle. Energy is, after all, used to do work. In the US or in China, a similar amount of energy lights a room, cooks a meal, or propels a car. And by that measure, the Chinese economy is already the biggest in the world. It uses more energy, it does more work. America is second best, and has been since 2010. It’s happened. Get over it. The fact that the U.S. uses more energy than China per person is beside the point—we’re talking about overall sums here. Of course, one could argue that the US uses its energy more efficiently. In the crude sense that’s untenable; although a US gas stove cooks more food per unit of energy than a Chinese coal stove, Chinese cars are more efficient than US ones, our energy is often wasted on pointless “work” like insane commutes, and China clearly gets more work done without using energy (e.g., using human power instead of forklifts or tractors). A more sophisticated version of the same argument would be to say that the sort of work that the US does is more valuable per unit of energy than the sort of work that the Chinese do. So, for instance, the true value of an iPod is in the *intellectual* work that went into it–the design and the songs on it (both of which take comparatively little energy), while the actual physical bits of it, assembled at high energy cost in China, are just a vehicle for the intellectual content. Which is sort of true, maybe, but then there’s all of the valueless intellectual work that we do, like running hedge funds, managing endless layers of other managers, advertising sugary crap to kids, prosecuting drug users, and on and on. I don’t see any evidence that the US economy is any more efficient at doing what economies are supposed to do—make people better off, or at least producing actual goods and services that people want—per unit of energy than the Chinese is. So, assuming I’m right (which one should always assume): Why does this matter? Who cares who gets the bragging rights? Well, cast your mind back to the early 20th century. The British economy had dominated the previous century, but the German economy had overtaken it. Thing was, Britain had used its economic power to dominate the world politically, and was still trying to hold on to its political supremacy even as its economic supremacy slipped. That tension was one of the big factors underlying World War I. Today, China and the U.S. are in the same position as Germany and Britain were a century ago: the U.S. is trying to hold on to its political supremacy as its economic supremacy is slipping. That doesn’t mean that war is inevitable; it does mean that we are already in a new, less predictable world, and that we *will,* rather soon, have to make room for others at the top. If we’re smart, we’ll do it willingly and with good grace. If we’re not, we’ll still do it. Scott Reeder at the Atlantic has an article about how two sporting goods stores–Cabela’s and Bass Pro–have received massive doses of state and local taxpayer money. Basically, if these stores want to open in your town, they first demand all sorts of subsidies. Cabela’s, for instance, often gets the town to build parts of the store. And since the town owns them, the company doesn’t pay tax on those parts. In the past 15 years, Cabela’s has received $551 million, and Bass has received $1.3 billion. I only have one thing to add to the article: Bass is a private company, so I don’t know how much it makes, but Cabela’s profits are public knowledge. Since 2003, which is as far as the data I could locate goes back, Cabela’s has made around $750 million in profits (more or less; I was eyeballing). Now: The subsidies have averaged $37 million per year (551/15). Profits have averaged around $75 million per year (750/10). Or about twice the subsidies. To put it another way: half of Cabela’s profit has come from taxpayers. If you add the $400 million in Federal financing, it’s more than half. Now: This isn’t all that unusual, and the problem is not that businesses get government help (although no business should get as much as Cabela’s gets). The problem is when we pretend that only welfare queens, unionized teachers, and Solyndra get government help, and that private enterprise is a realm of self-reliant Ayn Rand heroes who make their own way in the world. So Mitt Romney just selected Paul Ryan as his running mate. In so doing, he just killed any chance he might have had of winning the election. I’m not the first person to say that, of course, but other people are focusing on Ryan’s policies. And sure, they’re horrific. But the real problem is not that his policies are toxic. The real problem is that Ryan *has* policies. What, you say? Let me explain: Ronald Reagan. Dan Quayle. George W. Bush. Sarah Palin. They were all totally clueless when it came to policy. Hell, of the four of them, only Reagan could make a coherent sentence. And they didn’t really try to hide it; they waved their ignorance proudly, like a flag. And one of them was on the GOP ticket every year, starting 1980. The only exception was 1996. Say what you will about Bob Dole and Jack Kemp, but neither is an idiot. And remember the 1996 election? It seemed like the Republicans weren’t even trying. They went through the motions, but the fire wasn’t there. The Republican base, which is reliably passionate (not to say rabid), just didn’t seem to get excited. Why not? It wasn’t like the Republican base liked Clinton—they hated him with the fire of a thousand suns. I think it was because the crazies who make up the Republican base want to vote for someone just like them, someone who doesn’t understand policy and doesn’t care. They need to see a moron on the ticket. (Call it identity politics with a vengeance.) The base may have agreed with Dole and Kemp’s policies, but the fact that the election was even *about* policies–that both Republican candidates went on and on about them–turned them off. So while the crazies may agree with Ryan’s policies (which are certainly crazy enough), that’s not the point. They don’t want to vote for some intellectual who keeps talking about policy, they want to vote for a cretin who doesn’t give a flying fuck about policy and doesn’t care who knows it. They won’t get excited for Romney/Ryan, as much as they hate Obama. And if they don’t come out to vote for Romney, they won’t be around for the Senate, House, and local races. Which is why I titled this “Why the Republicans just lost,” not “Why Romney just lost.” So: Not only did Romney disgrace himself by playing to the right-wing lunatics; he managed to screw it up. Yes, this will please his right-wing funders. But they were already his funders, already basically giving him blank checks; how much more funding will they give? If Romney was going to go down this path, he should have gone all the way and picked Bachmann or Ronald Reagan’s skeleton or Dan Quayle again. Instead, he pulled down his pants and bent over, but he won’t even get the reach-around he wants. Try to get that image out of your head. Andrew Leonard’s review of David Wessel’s Red Ink (which I have not yet read) gets to the heart of the problem of much of our discourse on the economy: Red Ink, according to Leonard, is a very useful guide to exactly what the problems are with the federal budget, explained in an even-handed manner. And as Leonard points out, that even-handed manner is the problem. For instance, remember the Medicare drug benefit? It increased spending—more than it had to, because the government was not allowed to use its buying power to negotiate with the drug companies—without raising taxes or cutting other spending. Unlike Obamacare, which is actually paid for. Except that if you listen to Republicans, it’s not. Leonard writes:

And then he gets to what I consider the meat of the issue:

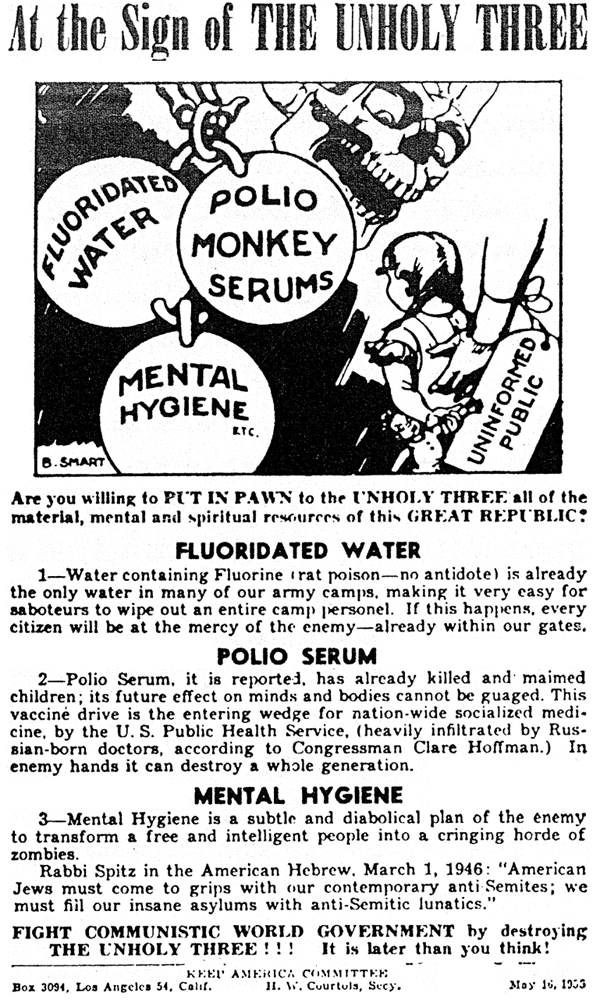

In other words, Wessel provides a lot of useful information about what happened, without the why. Which, really, is a rather good demonstration of the why; as Leonard says, one of our two political parties has gone nuts, but too much of our discourse—including, apparently, Red Ink, which I’m still going to read—politely ignores the fact that they’re nuts, and treats their insane programs as if they were not, in fact, insane. Well, y’all don’t have to worry about Economix, folks. I don’t shy away from finger-pointing. The recent news that fluoride in high doses—far higher than the amounts added to drinking water and toothpaste—is harmful to children’s brain development set off a new wave of conspiracy nuttiness; we might think of that as a revival of the lunatic fringe of the 1950s . . . .  But it’s never really died. Here’s a modern take. [2020 Note: I removed the link because it had broken and went to a payday loan site. Thanks, Derek! If you want to find a working fluoride conspiracy site just use Google.] Thing is, I tend to agree that it’s a bad idea to put a known toxin in the water supply, even at low doses. But water fluoridation was always a crazy magnet far beyond any danger of the fluoride itself. As Richard Hofstadter put it in the classic “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”:

Now: you’d think that anti-fluoridationists’ exaggerated vigilance at least would have an upside: that they’d always be on the prowl for any threat to our drinking water. For instance, hydrofracking: Right now, giant entities really are screwing around with our drinking water. And it’s not even a private industry vs government thing; government is in league with them, sometimes forbidding us from even knowing what’s in the chemicals we’ll be drinking. (And if you don’t think we’ll be drinking them, you’re listening to the wrong people.) But the people who flip out about fluoridation? They exist, and the batshit right wing that spawned them is stronger than ever. So where are they? Here’s a real-live problem, where dangerous chemicals really are being put into the ground where they will almost certainly wind up in our drinking water, and the antifluoridationists don’t lift a finger. Conspiracy crazies, I am very disappointed in you. I watched the live stream of Curiosity’s landing on Mars last night. For those of you unlucky enough to miss it, it showed the NASA Personnel at the Jet Propulsion Lab following the lander’s progress. It was incredible. The tension as the people who’d put years of work into a daring project—throwing a complex, fragile, car-sized machine at a planet—finally waited to see if they had done every single thing right. The small bursts of joy as preliminary stages went off without a hitch. The final celebration when it landed perfectly. The satisfaction on their faces as they allowed themselves to realize that they had done something nobody had ever done before. That they had done something for all of us. And I thought: Are we really trying to cut the budget for things like this? Why? Oh, right, we can’t afford it. Our society needs to save its resources for other things. Things like private jets, so that rich people don’t have to go through the hell of flying first class. Things like pills that turn your poop gold. Things like 100,000 varieties of shampoo. (I’m not exaggerating. A search on “shampoo” on Amazon gives more than 100,000 results.) And of course, the ads that make us care about 100,000 varieties of shampoo in the first place. God forbid we should go without those. Seriously, when did we decide that our highest, our noblest, our only possible task is producing more consumer products? Economix just got its first review! A good one! From Bob Greenberger! This is a good day. We’re constantly hearing about how rich people are wealth creators, job creators, the most productive members of our society, a bunch of Hank Reardons, bla bla bla ad infinitum, and how we should cut their taxes so that they can unleash their productive powers. The more intelligent-sounding purveyors of this point of view use sophisticated economic models to support their claims. But models are just that—they’re models of what should happen, given certain assumptions. And the real world is far more complex than any model can portray. The real way to understand what cutting taxes on the rich would do is: try it and see what happens. But I don’t recommend doing that. Why not? Because we already freaking did it. Many times. We know what happens when we cut taxes on the rich; we just choose not to remember. Thing is, back in the 1950s and 1960s, taxes on the rich were very high. Past a certain point, the government took almost all of your additional income—as much as 92 cents on the dollar. Yes, there were deductions; nobody paid 92% of their income. But a rich person deciding whether or not to earn an extra dollar had presumably already found all the deductions he could, so he really was faced with the prospect of working harder in order to earn only a few more cents. So back then when rich people said, hey, we would work harder and create more wealth if we were allowed to keep more of the reward, they were making a plausible argument. In fact, it was so plausible that we believed them and cut taxes. First to 70%, and then way below that. Meanwhile, we accepted higher taxes for ourselves and fewer services from government. So what happened? Here’s the maximum tax rate—the tax paid on income in the highest tax bracket—over time. Note the big cuts in 1964 and in the 1980s, followed by Clinton’s 1993 tax increase, followed by Bush’s cuts.

Now: If low taxes on the rich do what conservatives say, GDP should have been higher when the top tax rate was low, and lower when it was high and job creators were oppressed. So here’s economic growth by year, courtesy of the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Huh? All that up and down is hard to track. So let’s average economic growth over the relevant periods, which are:

Here’s what the averages look like.

Just to make things clearer, let’s put both lines together (ignoring the scale—we’re just looking at the pattern, not the absolute number):

Well, hell. So low taxes for the rich haven’t been good for the economy. The association goes almost exactly the opposite way. And still the rich say that cutting their taxes will unleash their dormant productive powers. But if it hasn’t happened yet, it’s not going to happen. The only thing we can conclude is that rich people give themselves too much credit. Now: You can play around with the exact periods you choose to average the data over, but the overall pattern will hold. For instance, if you say that we should exclude the current economic mess (everything after 2006, say) because its causes are clearly much bigger than just the Bush tax cut, we get this, which is even more exact:

Heck, just to show I’m not cheating, here’s every data point since 1951 (the line was drawn by Excel, not me):

[EDIT: I used Excel to get the correlation coefficient of that (0.21), transformed that into a t, and then got the p value of the t, which is apparently legit. The p value I got, assuming I did all the math correctly (it’s entirely possible that I didn’t) was 0.096 (which matches my eyeballing, more or less). That’s means that the observed correlation (high taxes are correlated with high growth) could have been just statistical noise, but there’s roughly a 9 in 10 chance that it wasn’t and that high taxes are really connected in some way with high growth. This is what statisticians call a “trend,” which is statspeak for, yeah it tends that way but you haven’t really shown anything. You need a 19 in 20 chance before a statistician will accept it as proof. [EDIT of the edit: Not “proof” exactly, as Reddit user Konchshell points out–rather, worthy of notice.]] Other people have cut the data in different ways and gotten the same result. They shy away from concluding that tax increases help the economy, and they’re right: none of this proves that tax cuts for the rich are bad for the economy, or that high taxes are good—there may have been other factors (like oil prices) that were more important. For that matter, it’s still possible that rich people really are job creators, and that they create more jobs when they’re motivated, but that high taxes are what motivate them. After all, rich people’s lives are almost all carrots and very few sticks; maybe the occasional blow from a stick will spur them to action more than another truckload of carrots. But all of this is beside the point. The point is that it’s simply impossible to look at the data and honestly think that cutting taxes on the rich will help the economy. [EDIT: user Konchshell on Reddit points out that it’s not in fact impossible, which is true–I’m overstating it. But still] That leaves one thing we can safely predict about taxes on the rich: They will bring in revenue. We could use some revenue right about now. No wonder conservatives always argue about what some model says should happen. The last thing they want is a discussion about what has happened. |

|