By Mike Welcome back to our exploration of the principles of economics in N. Gregory Mankiw’s Principles of Economics. We’ve been going for a while; start from the beginning here.

And we’re done with the principles themselves. Finally! All we have to do is sum up. If you’ve been reading so far, you won’t be surprised that summing up will take a while.

Let’s start by listing Mankiw’s principles that are neither wrong or misleading (defining “misleading” as “Mankiw gets the explanatory text wrong”). In other words, let’s take out the principles that are not actually principles. We’re left with:

- The cost of something is what you give up to get it.

- Trade can make everyone better off.

Ooh, fascinating.

And there are also sins of omission. Here are some “principles” that are at least as valid as anything in Mankiw’s list but that don’t appear there (or anywhere in his book, as far as I can tell from skimming it very very fast). These are off the top of my head:

- A dollar does more good — that is, it buys more utility — in the hands of a poor person than a rich person; the difference may well outweigh the harm done in taking it from the rich person.

- Cutting taxes on the rich does not in itself spark employment or economic activity.

- Wall Street is full of dangerous idiots who need to be watched every minute.

- Since 1940, the military budget has been arguably the single biggest fact in the American economy, and any textbook that barely mentions it [seriously, I can’t even find it in the index] is describing something other than the actual economy.

- The economy is not Newtonian physics, and thinking about it in terms of abstract principles can do more harm than good.

- “We can have democracy, or we can have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we cannot have both.” — Louis Brandeis

- Good economists try to learn about the complexity of the real world, while the bad ones pat themselves on the back for understanding abstract principles (and then they may not even understand them better than anyone else).

- Every economic system, no matter how unjust or inefficient, will produce people who try to justify it, people like N. Gregory Mankiw.

Of course, one can argue against every one of these, and against each of my takedowns of Mankiw’s principles. But that’s the point — Mankiw pretends that he’s presenting principles — settled facts — when he just plain ain’t. It’s really not too much to say that between Mankiw’s errors and omissions, a person who reads his principles will actually understand less about the real economy than before she cracked the book at all. And if you think that’s mere rhetoric, why, Mankiw agrees with me, although he doesn’t realize it. Check out:

The broken windows fallacy fallacy

There’s a sidebar in this chapter, “Why you should study economics.” Here Mankiw is quoting Robert McTeer Jr., former head of the Dallas Fed. McTeer’s example of why you should learn economics is the “broken windows fallacy” — the idea that if you, say, break a baker’s window, the baker will have to spend money to have it repaired, money that will then be re-spent, and so on, so breaking windows is good for the economy.

McTeer explains this is a fallacy because the baker would have spent that money on something else instead. He may buy a new window, but not a new suit. Economists understand that, ordinary mortals don’t, and that’s why we should learn economics.

But while McTeer’s logic might be more or less true if we were living in a textbook free market, things change when we’re dealing with the modern economy. If you went out and broke all the windows at an Apple store, Apple would spend money to repair them. Would it take that money away from other spending — spending that we know Apple finds useful, because why else would it be spending it — or from the $159 billion in cash that it literally doesn’t know what to do with, cash it’s just sitting on?

Or think about Christmas sales. If the broken window fallacy were actually a fallacy, then we (or at least the economists among us) would mourn when retailers reported good Christmas sales, because it would mean we were spending money on trivial gifts rather than on investment or useful items. But we understand that good Christmas spending means sales and jobs that wouldn’t just magically show up in another part of the economy. Because duh.

That is, we understand it unless we’ve read Mankiw’s textbook, which replaces our correct understanding with error. I’m not cherrypicking — Mankiw chose this as the very best example of why you should learn economics from him. It’s actually horrifying when you think about it.

Oh, and once again we’ve got a political statement posing as a neutral one. I could go into how this vision of the economy leads, by inexorable logic, to the idea that rich people are wealth creators, but I’ll spare you. Trust me, it does.

Now you may answer that I’m just arguing from logic (what Apple should do), which makes me no better than Mankiw and McTeer. Where’s the evidence?

My evidence is the long depression we’re in right freaking now. Thing is, if you believe that the broken windows fallacy is actually a fallacy, it follows that a long depression isn’t possible (because money is always spent for something, creating jobs), and therefore policy designed to create jobs is misguided. I wish I was reading between the lines here, but McTeer actually says exactly that, and Mankiw quotes him:

The broken window fallacy is perpetuated in many forms. Whenever job creation or retention is the primary objective I call it the job-counting fallacy. Economics majors understand the non-intuitive reality that real progress comes from job destruction [because it frees people up to do other things]. . . . We will occasionally hit a soft spot when we have a mismatch of supply and demand in the labor market. But that is temporary.

Granted, my edition of Mankiw’s text dates from 2008, but the 2011 edition (judging from the Amazon preview) hasn’t changed, even as a) even in 2010, when Mankiw would have turned in his manuscript, this depression was clearly something worse than a soft spot resulting from a temporary mismatch of workers and jobs, and b) the countries that followed economic orthodoxy and waited for the magic of the market to solve everything are, by and large, the ones that have suffered the most.

By the way, I was working from an old text because the 2014 edition (which has no preview on Amazon) has a list price north of $360. Mankiw can charge such prices because each generation of students is forced to buy the newest version, whether or not anything has changed from the previous edition (remember how we’ve seen lines that were clearly from 1991 or so and never updated).

And hey, that’s an example of another principle: the people who preach the discipline of free-market competition can preach it fervently because they don’t have to fear being subjected to it themselves, whether they’re corporate bureaucrats, politicians, “thinkers” in the warm embrace of the conservative idea factory, or tenured professors like Mankiw with guaranteed buyers for their overpriced texts.

Now: I don’t believe that Mankiw is stupid. And that’s the problem. He didn’t write this textbook from scratch after a lobotomy; he learned its worldview in his Econ 101 class, reading a textbook written by someone who learned it from a previous text, all the way back to David Ricardo’s Principles of Political Economy and Taxation in 1817. Once he learned that framework, he fit everything he learned afterward into it. This is called motivated reasoning, and it has nothing to do with intelligence. In fact, Mankiw’s brainpower probably makes it easier for him to be wrong: smart people are good at finding justifications for conclusions they came to for nonsmart reasons. Think of a brilliant theologian, subtly defending propositions that are ridiculous when you state them plainly (big man in the sky rules the universe but also cares deeply whether your peepee goes into someone else’s poohole).

Mankiw even gives a good description of the scientific method, how economists should use it (by looking at the “natural experiments” of history), and how they should use assumptions and models (with full understanding that they do not describe the real world; as Mankiw says of plastic models of the body, they’re useful simplifications but “no one would mistake one of them for a real person” ). He can write this and somehow just not see that he ignores the real world, and mistakes his models and assumptions for it, all the damn time.

And now Mankiw is teaching this mental framework to a new generation, who will spend the rest of their lives finding ever-more-clever ways to ignore its flaws. Or they’ll drop out of the field in disgust, which serves the same purpose; either way, the institution of economics goes on as before and nobody is forced to think hard about the rottenness at its core.

What’s the solution?

Well, in an ideal world every econ 101 class would use Economix instead of a textbook like Mankiw’s. (In fact, that’s pretty much the beginning and end of my definition of an ideal world.) But realistically, schools didn’t hike tuitions to today’s ridiculous levels in order to teach from comics that anyone can just read, so what we need is better textbooks.

And there are better textbooks out there. Samuelson and Nordhaus avoids some of Mankiw’s mistakes (although it’s not nearly as good as the first edition, published all the way back in 1948). And I haven’t read Krugman, but no doubt he’s better too (he doesn’t believe that broken-window drivel, for one). James Galbraith, son of the great John Kenneth, has a textbook as well, and I’m sure that it’s pretty decent.

So if your class is forced to buy Mankiw instead of a better text, complain. If nothing else, you’ll bring the political bias in your econ department out into the open.

It’s also worth complaining to authors and publishers. There are worse textbooks out there as well (I selected Mankiw because he’s typical, not because he’s an particularly mendacious), and complaining does have an effect. Econ professors are, as might be expected, generally not the most rugged of personalities. Mankiw, for instance, in his first edition famously called the Reagan advisors who said cutting taxes on the rich would bring in more revenue (they really said this, and Reagan really believed, it, or pretended to) “charlatans and cranks.” It was a fair and accurate description, but he removed it when a couple of people complained.

And Samuelson and Nordhaus isn’t as good as Samuelson’s first edition from 1948 because conservative complaints in the 50s or 60s (I can’t find my source dammit) induced him to change it from liberal-leaning to center-conservative.

Point being, if publishers start to see the shittiest textbooks — the ones that present the conservative worldview as settled fact — selling less and causing complaints, they’ll fall over themselves to produce better ones. It’s hard to change an institution, especially one so ossified as the economics profession, but this is the way to start.

Finally, although I don’t generally plug products, I’d like to put in a word for Peter Dorman’s Macroeconomics: A Fresh Start and Microeconomics, A Fresh Start. I’ve only read excerpts, but what I’ve seen is impressive: they emphasize history, they teach the models but also their limitations, and they’re just plain well written. Dornan really does seem to have tried to start from scratch and to reject what doesn’t make sense anymore (or never did).

They’re also, together, less than half the cost of Mankiw’s textbook.

A better product, for less money. If Mankiw’s Principles of Economics was right — if the economy really was a free market, ruled by competition — nobody would buy it.

By Mike And we’re back. We’re looking at the 10 principles in N. Gregory Mankiw’s Principles of Economics; We’ve covered 7 of his 10 principles already. Start at the beginning here.

Part 2 is here.

Part 3 is here.

Part 4 is . . . wait for it . . . here.

Today let’s check out:

Principle 8: A country’s standard of living depends on its ability to produce goods and services.

As Mankiw makes clear in the explanatory text, this means that our standard of living depends on our productivity. If we don’t make more pie, we can’t get more pie. And obviously, this has policy implications. Here’s Mankiw:

When thinking about how any public policy will affect living standards, the key question is how it will affect our ability to produce goods and services.

Sounds sensible, right?

But it’s not just important to make the stuff, it’s important to distribute it. If we only think about how a policy affects the size of the pie, we might sign off on policies that make one group’s slice bigger and don’t increase — or straight-up shrink — everyone else’s share. Which is, basically, the story of the last 40 years of American economic policy. Most of us don’t live any better than we used to, while a very small number of people live in insane luxury — so much that they would probably be better off if they had less.

Mankiw doesn’t mention this. Oh, and he doesn’t mention that some of our goods — clean air, clean water, etc. — aren’t so much produced as just there, and that many of our biggest problems are consequences of our high productivity — our ability to strip entire forests, to cover the landscape with tarmac, to burn coal until the trace mercury in it winds up poisoning the fish we eat, to pull all the fish out of the ocean, to pump CO2 into the air until the sea drowns our coastal cities, and so on.

Grade: C+.

Not wrong, exactly, but with big omissions that make it misleading when elevated to a principle. And once again, the omissions are political and on the side of the status quo: if the “key question” for any policy is its effect on the size of the pie (rather than on the size of the slices, or on the environment, or on the functioning of our democracy even), and if redistributing incomes shrinks the pie (which Mankiw already said), then policies that threaten Paris Hilton’s ability to spend a quarter-million dollars on an evening clubbing are a no-no. Q.E.D.

Suggested replacement principle: A country’s standard of living depends in large part on its ability to produce and distribute goods and services.

On to:

Principle 9: Prices rise when the government prints too much money.

Well, duh. “Too much money” is by definition the amount of money that causes prices to rise. (To rise more than we’d like, that is; a little inflation can be a good thing.) So this is just another tautology.

And yet, once again, Mankiw somehow manages to be misleading. How are we supposed to read that except as “when prices rise, the government has printed too much money”? And that just ain’t the case. Prices can rise when money stays constant but some people charge more for their products (like when there’s a bad harvest, or Saudi Arabia cuts oil production, or Bank of America decides to raise its fees because they want your money and fuck you).

Heck, it’s easy to misread this principle as “when governments print more money, the only result is that prices rise.”

Grade: D+.

I probably would have given this a better grade earlier on, but I’m getting tired of watching Mankiw give tautologies as principles, and then manage to somehow screw them up. It takes a weird kind of skill to flub a tautology.

Also, that last misreading? “When governments print more money, the only result is that prices rise”? It’s not really a misreading. Mankiw actually believes it. Check out:

Principle 10: Society faces a short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

This is, on the face of it, true and important. If the government prints money (and gets it into people’s hands, a crucial step we forget today when we simply make it available to banks), we’ll spend more. This will normally have two effects: sellers will produce more to sell (hiring people in the process and reducing unemployment) and they’ll increase their prices (because they can and they’re not stupid). How much they do of each will depend to some degree on how much slack capacity there is in the economy.

So printing more money is a good idea in times of high unemployment but will spark unwanted inflation if you do it when the economy’s already going full blast. This isn’t just theory; the tradeoff — the Phillips curve — shows up in the real world again and again. It’s not an unbreakable rule (the stagflation of the 1970s didn’t follow it) but it is a definite pattern, which is about as good as it gets in economics.

So what’s the problem? It’s the term “short run.” What happens in the long run? According to Mankiw: “A higher level of prices is, in the long run, the primary effect of increasing the quantity of money.”

That makes sense until you think about it. Look at it this way: In the short run, if you print money, you increase economic activity and decrease unemployment. People can afford to educate themselves better, get better medical care, eat better, and remain non-homeless. They’re less stressed (which means their freaking brains don’t shrink), commit suicide less, and so on. Meanwhile, sellers faced with increased demand do their best to find more efficient ways to produce (creating new inventions that bring down prices in the future). How in God’s name does that all just automatically disappear in the long run, replaced by an economy that looks like what it would have looked like anyway but with higher prices?

Duh, it doesn’t. Increasing the money supply can increase prices to match in the long run, but it doesn’t have to, and even when it does, just because the general price level is higher doesn’t mean that that nothing else has changed.

Now: sometimes the experience of the 19th century is given as evidence for this “principle.” Back then currencies were backed by gold and the general price level, although it fluctuated wrenchingly year by year, didn’t vary in the long run. Gold is constant, prices were constant, Q.E.D., right?

But gold wasn’t constant. In the 19th century we stripped entire continents of their gold (think of the gold rushes in the Yukon, California, Australia, Colorado, and especially South Africa), multiplying the gold supply faster even than population rose, which had the same effect as printing money. So we increased the money supply and prices didn’t rise in the long run. This is evidence that a higher level of prices is not “in the long run, the primary effect of increasing the quantity of money.”

So where did this dumb idea come from? It’s another example of how hard it is for economics to get away from old bad ideas. The idea of “monetary neutrality” — that changing the money supply changes prices and nothing else — was just an axiom in the 18th century, asserted without direct evidence. But we can excuse that; good economic data were rare back then.

Then, over the next couple of historical epochs, evidence came in showing that changing the money supply does in fact affect the real economy, as common sense would suggest, to the point that (some) economists accepted it.

But the evidence was clearest in the short term — there are a million confounding factors in the long term — so economists continued to believe that the long-term effect is neutral, even though the idea that there’s a short-term effect and no long-term effect is freaking absurd. And they continue to believe it to this day, even as long-term evidence to the contrary has come in.

Oh, and once again, this is a political statement masquerading as science (“sure, expansionary policy can help the economy in the short term, if you only care about that, but you shouldn’t bother because in the long term all of those effects magically vanish.”)

Grade: C-.

The principle itself is broadly true and useful, but the more Mankiw tries to support it the more wrong he gets.

Suggested replacement principle: “Society often faces a trade-off between inflation and unemployment.” No “short-term”, and adding “often” leaves open the possibility of other situations (e.g., stagflation).

Phew! We’re done. Those are Mankiw’s principles.

Onward to our gripping conclusion!

By Mike Welcome back to our examination of N. Gregory Mankiw’s textbook. Start at the beginning here.

Part 2 is here.

Part 3 is here.

Okay, we’re starting the section “how people interact.” It’s probably the best section.

Let’s jump into:

Principle 5: Trade can make everyone better off.

This is true and not entirely commonsensical (many people think that if, say, Japan gains from trade with us, we must be losing an equal amount from trade with them). Even better, the explanatory text is clear and reasonable, and the “can” keeps it on this side of the line between reality and dogma (trade doesn’t always make people better off).

Grade: A.

Suggested replacement principle: None.

Wow! That was so quick, let’s get ambitious and take on two at once:

Principle 6: Markets are usually a good way to organize economic activity.

And, Principle 7: Governments can sometimes improve market outcomes.

Both are true, both are important, and each is a corrective for the other. It looks like Mankiw is on a roll.

But then there’s the explanatory text. Oy, the explanatory text.

It seems okay at first. Mankiw praises the invisible hand of the free market (as he should), and then explains, rightly, that we need government both to enforce “the rules and maintain the institutions that are key to a market economy” and because markets, left to themselves, don’t always work.

And when he explains two big reasons why markets break down (externalities and market power), he’s clear and correct.

SKIP THIS PARAGRAPH IF YOU UNDERSTAND THE ABOVE CONCEPTS. If you don’t: Externalities occur when people who don’t take part in a transaction are affected. So if Georgia Pacific decides that it wants $10 more than it wants a ream of printer paper, and I want a ream of paper more than I want $10, the transaction makes us both better off, and thus society is better off because its members are. It follows that if we leave people free to choose their own transactions, everyone will do what makes them well off, and the result will be the choices that are best for society. But if GP pollutes your air while it’s making my paper, you’re worse off and society is less well off (and possibly absolutely worse off) because you’re also a member. But you had no say in the deal. At that point, the outcomes can be improved if government, say, taxes pollution. Market power matters because a free market is regulated by competition (If I run a bar and sell watery beer for $40, you’ll open a bar and sell good beer for a good price and I’ll go out of business), and this regulation is preferable to government regulation in several ways (like, no bureaucrats to enforce it). But if a company has the power to avoid competition, like if Bank of America decides to raise its fees because screw you, then the argument against government regulation evaporates. At that point, the outcomes can be improved if government, say, breaks Bank of America into tiny little competitive pieces, like an ogre crushing bones into dust, while the shareholders scream in impotent outrage and . . .

Anyway. So far there’s nothing to object to. What’s the problem?

The problem is that as Mankiw continues, it becomes clear that his understanding of the economy is just plain crude. He really seems to believe that the economy actually is a textbook-perfect free market, with the occasional exception where government can step in (otherwise government has little to do except protect property and enforce contracts). That just ain’t the case.

First off, market failure isn’t some occasional exception. We live in a world of externalities, from the plastic bags in the Pacific to the hormones and antibiotics in our food to the slow-motion environmental horror we’re just starting to taste. And we live in an economy of big corporations, not little scrappy lemonade stands, and the big corporations are big because it gives them market power (and also because it’s easier for them to externalize their costs, from pollution to dead workers).

Second, while our governments don’t do what they should to prevent or fix these problems, they’re hardly afterthoughts in the economy. As the economist Robert Heilbroner put it, “the state, both as defender and promoter of the economic realm, has played so prominent a role that even the most abstract scenarios of the system unwittingly assign it a central and indispensable place when they take as their unit of conceptual analysis the state.”

It may seem like I’m being unfair. Surely Mankiw, a Harvard econ professor, doesn’t really think that the economy is a textbook free market, right?

But what else can we think when Mankiw says “taxes adversely affect the allocation of resources, for they distort prices and thus the decisions of households and firms”? That only makes sense if the economy — the one we actually live in — is so perfectly balanced that any change is a distortion. In reality, the economy is a messy place, already distorted from the textbook ideal (so much so that it’s just a different beast); there’s no reason that a given tax automatically distorts it more.

And what are we to think when he talks about “the great harm caused by policies that directly control prices,” without a single caveat? (Medicare uses price controls and, far from causing “great harm,” works better than private insurers, who often behave like a cartel).

Heck, what else are we supposed to think, five pages into the next chapter, when Mankiw diagrams the economy and doesn’t include government in the diagram? No taxes, no government spending, just households and firms.

Or when he explains how the collapse of the Soviet Union represented a victory of market economies (“where the decisions of a central planner are replaced by the decisions of millions of households and firms”) over centrally planned ones? Really the governments of the West were mixed economies, where planning (in the US including such Stalinist horrors as Social Security, Medicare, highways, zoning laws, building codes, product quality laws, sewers, restrictions on advertising, public health programs, air and water protections, schools, banking regulations, street cleaning etc. etc. etc.) coexisted with markets.

True, everyone was talking bollocks about the unqualified triumph of capitalism over communism after the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union withered away. But since then:

- Russia listened to free-market economists, adopted straight-up market economies, and got economic collapse, oligarchy, and dictatorship (in that order)

- China (where the state, flawed and corrupt as it is, kept a firm hand on the economy) blossomed, despite starting from a much lower level than Russia

- The West changed its public-private mix to be less public and more private.

- We are now many years into a depression that free-market economists said was impossible.

But lines like “many countries that once had centrally planned economies have abandoned the system and are instead developing market economies” read like they haven’t been updated for more than 20 years.

My point is not that the idea that government should protect property, enforce contracts, step in when the market has clearly failed, and do very little else is wrong. I think it is, but that’s not the problem. The problem is that it’s a political point of view, not settled fact. Once again, Mankiw has dressed up a political agenda as neutral scholarship.

Grade: C. Maybe I’m being generous, but someone who just skims the principles themselves will learn something. But if they read the explanatory text to understand why these principles are true (as any good student should) they’ll get a worldview that seems frozen at the conventional wisdom of 1991.

Suggested replacement principles:

- Markets are usually a good way to organize economic activity.

- Well-designed policy can improve market outcomes, keep markets functioning, and replace failing markets.

- Government is inextricably woven into our economy on every level, for better or worse.

That’s all of “How people interact.” Although again, we’ve barely scratched the surface of how real people interact in the real world.

Tune in tomorrow (or soon after) as we start on the next section, “How the economy as a whole works.” And hooboy. Brace yourselves. It’s here.

By Mike Welcome back to our examination of N. Gregory Mankiw’s “ten principles of economics.” (Part 1 of this series is here; Part 2 is here). We got through two principles last time, but today we’ll only manage one. It’s a big ‘un:

Principle 4: People Respond to Incentives

An incentive is, according to my computer’s dictionary, “a thing that motivates or encourages one to do something.” So people respond to incentives, which are things that people respond to. This is a tautology rather than a principle.

Of course, there’s more to it. In the explanatory text, Mankiw points out that keeping incentives in mind is crucial when designing public policy (which is true — unintentional incentives in the tax code in Sweden led to the horror that was Abba’s outfits), and that, for example, a gasoline tax would likely encourage people to use less gasoline (also true). But then he gives this example, which I’ll quote in full.

When policymakers fail to consider how their policies affect incentives, they often end up with unintended consequences. For example, consider public policy regarding auto safety. Today, all cars have seat belts, but that was not true 50 years ago. In the 1960s, Ralph Nader’s book Unsafe at Any Speed generated much public concern over auto safety. Congress responded with laws requiring seat belts as standard equipment on new cars.

How does a seat belt law affect auto safety? The direct effect is obvious: When a person wears a seat belt, the probability of surviving an auto accident rises. But that’s not the end of the story because the law also affects behavior by altering incentives. The relevant behavior here is the speed and care with which drivers operate their cars. Driving slowly and carefully is costly because it uses the driver’s time and energy. When deciding how safely to drive, rational people compare, perhaps unconsciously, the marginal benefit from safer driving to the marginal cost. As a result, they drive mroe slowly and carefully when the benefit of increased safety is high. For example, when road conditions are icy, people drive more attentively and at lower speeds than they do when road conditions are clear.

Consider how a seat belt law alters a driver’s cost-benefit calculation. Seat belts make accidents less costly because they reduce the likelihood of injury or death. In other words, seat belts reduce the benefits of slow and careful driving. People respond to seat belts as they would as they would to an improvement in road conditions–by driving faster and less carefully. The result of a seat belt law, therefore, is a larger number of accidents.

This sounds like blackboard bullshit, but there’s actually empirical support for it (it’s called the “Peltzman effect” from the person who found that yes, people take bigger risks on the road when they feel safer.) My favorite example of the Peltzman effect, as long as we’re talking about Sweden: Sweden switched from driving on the left to driving on the right, overnight, in 1967. Everyone expected a wave of accidents, but instead accidents went down because drivers were paying more attention. Note that this means that we don’t calculate risks exactly–drivers overreacted in that case.

But Mankiw makes it sound like government efforts to improve road safety have been, and must be, futile because drivers will simply adjust their driving to keep the risk constant. That just plain ain’t the case. I’ve read Unsafe at Any Speed, and here are some other problems with Detroit’s cars back then, besides the lack of standard seat belts:

- If you were one of those safety-conscious people who had paid extra for a seat belt, a head-on collision could insert the steering wheel into your face (the steering column was one piece, instead of two shorter pieces connected by a gear).

- Even if that didn’t happen, your seat might break off, hammering you into the steering wheel.

- Brake fluid had a tendency to boil, leaving the brakes useless. By the time anyone checked at the accident scene, the fluid would have cooled, leaving no evidence except the driver’s word.

- The snazzy designs of yesteryear left big blind spots (and a few people were even impaled on those cool tailfins).

- Even outside rear-view mirrors weren’t standard (until 1966).

- In fact, the car companies had only adopted windshield wipers, directional signals, and brake lights (which were standard by the time Nader was writing) under compulsion from the government.

The car companies insisted that they simply couldn’t fix these problems (although somehow they found the resources to completely redesign their cars every year); they only did fix them when government action, or the threat of it, forced them to.And if you think it’s unlikely that we’ve let our driving deteriorate to the point that we’ve offset all of these reduced risks (many of which drivers in the 1960s didn’t even know about), you’re right. Driving is much safer than it used to be. It’s worth remembering just how deadly driving used to be — the economist John Kenneth Galbraith wrote in the 1950s of an “annual massacre of impressive proportions,” and a British person in the 1960s said, “I drive every day. I see blood on the road every week.”Government doesn’t get all the credit; cultural changes have mattered as well (when I was a kid, if you got into an accident, “I was drunk” was considered an excuse). Still, it’s no secret that “the Peltzman effect” does not equal “regulations are futile.” Here’s a 2006 meta-analysis:

As Peltzman (1975) acknowledges, offsetting behaviour could be trivial or substantial. Indeed, the amount varies between road safety measures. Behavioural adaptation generally does not eliminate the safety gains from programmes, but tends to reduce the size of the expected effects.

And that person who saw blood on the road? He was quoted in Richard Titmuss’s The Gift Relationship (1968), describing why he gave blood regularly. And Titmuss’s book is relevant to this discussion. It showed how the blood supply in Britain, where people donated for free and where the distribution was done by a socialist bureaucracy, was cheaper and better than in America, where donation and distribution were rewarded with money. A reviewer summarized the message of the book:

For a lesson in modern political economy, consider the trade in doolb. In the land of Niatirb, the supplie[r]s of this vital commodity receive no pay, and its processing and distribution are in the hands of government bureaucrats. In Acirema, by contrast, nearly all doolb supplie[r]s receive cash or other tangible, individual incentives, and much of the processing and distribution is carried out for profit. Obviously, Acireman doolb supplies will be higher in quality, lower in price, more accurately attuned to demand, and involve far less wastage—right? Wrong.

Point being, “incentive” is a broad term. The desire to do good is an incentive as much as the desire for money. People gave more blood in Britain, where giving was a noble, selfless act, than in America, where it was a troublesome way to make a couple of bucks.

Mankiw doesn’t deny this, but he doesn’t mention it, either. It’s easy to misread this section as saying that our individual, selfish gain/loss calculations are all that matter.

And Mankiw doesn’t mention that taking incentives into account doesn’t always work. Consider crack cocaine. When it first appeared in American cities in the early 80s, it was new, it was scary, and a (somewhat justified) moral panic ensued. The result was the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which imposed wildly disproportional penalties on crack (100 times those for a similar amount of powder cocaine). I’m old enough to remember that the idea was to stop crack from spreading. Addicts were expected to look at the incentives and say, “heck, it’s just not worth it. I can get as high as I want to on heroin.” To put it mildly, that didn’t happen. We can conclude that people become crackheads for some reason other than a rational cost-benefit analysis.

And it’s not just crackheads. The Earned Income Tax Credit is a helpful subsidy for the working poor, but that doesn’t mean that people take its incentives into account when making life decisions:

“I mean, Earned Income Credit is nice, but it’s not everything!” said one 25-year-old mother of three. “I’m not going to let it factor into my marriage if I ever want to get married. I’m not marrying the Earned Income Credit. I’m marrying the man I love.”

I’m not creating a straw man here: a lot of public-sector reform in the English-speaking world, and the countries we bully, really has been based on the idea that monetary incentives trump everything. Many still cling to this idea in the face of the fact that these “reforms” haven’t actually made things better.

Grade: C-.

The principle itself is a dull tautology, redeemed in part by some clear explanation of policy consequences, but even that winds up being misleading.

Suggested replacement principle: “Human behavior is a complex thing that is only partly explained by measurable incentives.”

It’s worth pointing out that Mankiw’s errors and omissions so far have all pointed in the same direction–toward a defense of the status quo (redistributing income reduces the size of the pie so don’t bother, environmental regulations do the same so don’t bother, and safety regulations lead to offsetting behavior so don’t bother). We’ll be seeing more of that.

The first four principles were categorized as “how people make decisions,” although they barely scratched the surface of how people actually make decisions. The next three are “how people interact.” We’ll start with them tomorrow.

On to the next post!

By Mike (See Part 1 here).

Okay, we’ve made it through Mankiw’s Principle 1. Onward to:

Principle 2: The cost of something is what you give up to get it.

This sounds like plain common sense, but it’s actually not — Mankiw is talking about the economic idea of “opportunity costs,” which is a more exact way to think about costs. The point is that we shouldn’t analyze costs and benefits in isolation — we have to look at the costs and benefits of the alternatives as well. So, as Mankiw explains, including room and board in the cost of college can be misleading, because you have to eat and sleep either way.

Grade: B.

Nothing worldshaking, but it’s something the reader didn’t necessarily think as clearly about before.

Suggested replacement principle: None.

That was quick. Let’s try another:

Principle 3: Rational people think at the margin. Thinking at the margin means, for instance, taking into account how much of a thing you already have before you buy another. So you might decide that buying a family car is worth the cost if you already have one, but not if you already have three, even though the fourth is the same price as the first three were.

And here’s what Mankiw has to say about rationality:

Economists normally assume that people are rational. Rational people systematically and purposefully do the best they can to achieve their objectives, given the available opportunities.

That’s common sense, right? If your shoes have holes in them, you don’t buy an apple or a ranch, you buy new shoes.

But actually, we *do* buy things that have no rational connection to what we actually want. Think of how things are advertised to us. Yes, sometimes ads inform us that something exists, or that it’s cheaper in one store than in another. But often ads try to associate their products with an image that is designed to bypass our rational mind. And these ads work. So we go to McDonald’s at least in part because of the fun times they show in the commercials, even though we rationally know we’re only going to get “the drab reality of fried meat” (to quote my favorite line in Economix). Or we buy Mountain Dew for the image of thrills, and get no more thrills than we would have otherwise. Or we buy yogurt when we’re really looking for friends. This is not rational, and hundreds of billions of dollars of ad spending suggests that it’s not trivial either.

Even when we want something for rational reasons, there are many ways we don’t go about getting it in the most rational way (Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow is a great source here). One big one I don’t think Kahneman mentions: We often think of our future selves in the same way we think of other people. So yeah, working out now will give me-in-the-future the big muscles that I want, but screw him. That ain’t rational, but it’s how we think.

Heck, have you ever done something stupid, knowing at the time it was stupid? That ain’t rational either.

For that matter, assuming rationality ignores that rational thought takes energy. So we know that there’s no difference between $3.99 and $4.00 when we stop and think about it. But that missing penny still makes us more likely to buy, because who has the energy to stop and think about it every damn time? Instead we glance at the price, think “three dollars something,” and buy. Heck, it’s not even rational to spend time and effort thinking about it.

Economists are well aware that there’s a problem with always assuming that people are rational, and are exploring more ways where strict rationality doesn’t apply. Mankiw doesn’t even hint at that. So:

Grade: C.

Suggested replacement principle: “It can be useful to assume that people are rational.” It’s not that assuming rationality is useless in all cases, it’s that Mankiw makes it sound like it’s how we should think about human behavior, and it just plain isn’t.

(As an aside, the contrast between economics and advertising is telling. Both disciplines deal with the same subject (how people make economic decisions), and in the 19th century both started from the prevailing idea that people were basically rational. So ads made rational appeals–product A is better or cheaper than product B. The ads often lied, but trying to mislead us with false information still assumes that we act rationally on that information.

But in the late 19th century, Freud showed some of the ways we’re not rational. And in the 20th century, led by Freud’s nephew Edward Bernays, advertisers learned to make image-based, emotional appeals to our irrational minds. Today, that’s what marketing is about — finding ways to make us love our iPhones rather than rationally compare them with Androids.

Meanwhile, economics went right on assuming people are rational.

The difference, I think, is that a new idea in economics is judged mostly on how elegantly it fits in with old ideas, which makes it pretty much impossible to move away from the old ideas (even as every other social science has managed it). By contrast, in advertising a campaign works — it motivates real people to make real economic decisions — or it doesn’t. And science, fundamentally, means checking your ideas against the real world, not against elegant intellectual structures people thought up centuries ago.

So advertising has changed, and economics hasn’t, because advertising is more scientific than economics.)

Anyway.

That’s all for today. Check in tomorrow for more.

On to the next post!

By Mike So a while back I posted about how economics education as it’s usually done can manage to be dull, misleading, and (covertly) political, all at the same time. Which is, after all, why I wrote Economix, which is not (I hope) dull or misleading, and is overtly political.

But there’s always someone who will say that any given criticism of the field, or part of the field, is unfair, that economists don’t really believe X or Y, that you’re taking something out of context or looking at the wrong source, and so on. And sometimes they’re right.

So I thought I’d look at N. Gregory Mankiw’s Principles of Economics. Mankiw (a Harvard professor) is the 29th most cited economist. If there’s a mainstream in economics, Mankiw is in it. His textbook is one of the most popular out there, and judging a field by its textbooks is at least as legitimate as judging it by its scholarly journals.

And we don’t even have to look at the whole book; Mankiw has thoughtfully provided us with with ten principles right at the beginning. This must be the very distillation of what Mankiw–and thus, a large part of the economics profession–thinks is important. Here’s Mankiw saying so:

The study of economics has many facets, but it is unified by several central ideas. In this chapter, we look at Ten Principles of Economics. . . . The ten principles are introduced here to give you an overview of what economics is all about.

Let’s take a look. This is going to be long, so I’ll split it into several posts.

Principle 1: People face trade-offs

This is a good, common-sense rule of thumb–every transaction, for instance, is a tradeoff between giving up our money and not getting the thing we want. But elevating it to a principle is a mistake. In another post I point out that we can sometimes find situations where there’s no tradeoff if we think more carefully. (Buying swirly lightbulbs is a tradeoff between higher up-front costs and lower electric bills, but those bulbs also pump less heat into your apartment. If you buy the swirly lightbulbs and a cheaper air conditioner than you otherwise would have, there’s no tradeoff–you get lower up-front costs and lower bills down the line). We generally don’t think like this, but that’s no reason to ignore the fact that there’s good reason to try.

Again, though, that’s okay as a rule of thumb. But Mankiw doesn’t just state principles; he gives explanatory text for each one. And in the explanatory text for the very first principle, he starts to get into real trouble.

All he’s trying to do is give examples of tradeoffs, and he gives a couple of good ones. But then he says that there’s a tradeoff between a clean environment and a high level of income. According to him, environmental laws increase the cost of producing goods and services, which means more expensive goods and services. (He also thinks that this means lower wages, but that’s silly–a plant that has to hire people to clean up its mess is paying more wages and driving the general wage level up.)

So is there a tradeoff? Sometimes, yes. But remember, waste isn’t just bad for the environment, waste is inefficiency. Reducing inefficiency can reduce waste and costs. For instance, have you noticed that soda bottle tops are smaller than they used to be? That means cheaper bottles (leaving us with more resources for other things) and less waste—when we throw the empty bottle into the nearest dolphin’s eye the dolphin is less hurt. Where’s the downside?

And what about using old fryer grease to power cars? That turns the waste into a resource, meaning less oil extraction, less global warming, and smaller fatbergs.

And in the real world, when nasty old government has twirled its moustache and forced innocent businesses to clean up their own messes, the results have been far better, and far cheaper, than expected–often just the unexpected benefits have outweighed the cost, which is pure gain for society. For instance (according to Barbara Freese’s book Coal):

One economic study found that the Acid Rain program’s improvement of visibility—a benefit barely considered when the law was passed—is alone worth the substantial cost of pollution controls, quite apart from the many environmental and other health benefits.

For that matter, there’s pretty good evidence that getting lead out of gasoline in the 1970s was a big cause of the reduction in crime in the 1990s (as the 1970s babies approached their high-crime years and just didn’t commit crimes, surprising everyone). If that’s even a little true, the purely economic benefits dwarf the costs so much it’s not funny. Literally not funny.

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that there is not always a tradeoff between a high level of income and environmental protection.

Speaking of efficiency, Mankiw also says that society faces a tradeoff between efficiency and equality. If you take that as a principle, then the most unequal economy is also the most efficient.

That sounds wrong, and it doesn’t sound any less wrong when Mankiw tries to explain it:

When the government redistributes income from the rich to the poor, it reduces the reward for working hard; as a result, people work less and produce fewer goods and services. In other words, when the government tries to cut the economic pie into more equal slices, the pie gets smaller.

This is of course true, in economies where equality is so extreme as to interfere with efficiency. So this is essential information for Mankiw’s many North Korean readers. But in other economies, like–to pull an example out of the air–ours, this doesn’t apply. My evidence is not some smug logic but the real world: Our economic performance, measured by annual real increase in GDP, has not improved as inequality shot up starting in the 1980s. It’s fallen off. It’s not 1-to-1; our economic performance has been falling off since the 1950s, while inequality only started increasing later. But still, where’s the evidence that more inequality is more efficient?

In fact, there’s pretty good evidence that the level of inequality we have is a drag on the economy.

And here’s something interesting: the two examples above are highly political statements posing as neutral, technocratic ones.

So this “principle” doesn’t tell us anything we don’t know, but still manages to be both wrong and political.

Grade: F.

Suggested replacement principle: “People don’t always face trade-offs.” That covers the fact that usually we do, for readers who have been lobotomized, and for the rest of us it’s at least a bit startling and gets us thinking in terms of finding win-win situations.

Phew.

Onward to part 2, here!

By Mike Behold, a comic that explains Obamacare (nearly to death).

It’s here: https://economixcomix.com/home/obamacare.

By Mike You can see it here: https://www.kosmas.cz/knihy/198734/ekonomix/!

By Mike Mother Jones today has one more reason not to buy bottled water: It’s coming from the most drought-afflicted regions of the country.

I’m not saying never buy it. If it’s hot, you’re thirsty, and there are no water fountains nearby, it can make sense to spend $1.50 for a bottle of water. It’s healthier than Coke, after all.

But seriously, if you’re buying it more than occasionally, stop. A little bit of planning (and filtering if the tapwater in your area doesn’t taste great) saves you money and doesn’t take water from where people actually need it.

By Mike Writing Economix took a lot of work—I started in earnest in 2004 and the book wasn’t published till 2012—and the whole time I had a rather loud voice in my head telling me that I was simply throwing away my life.

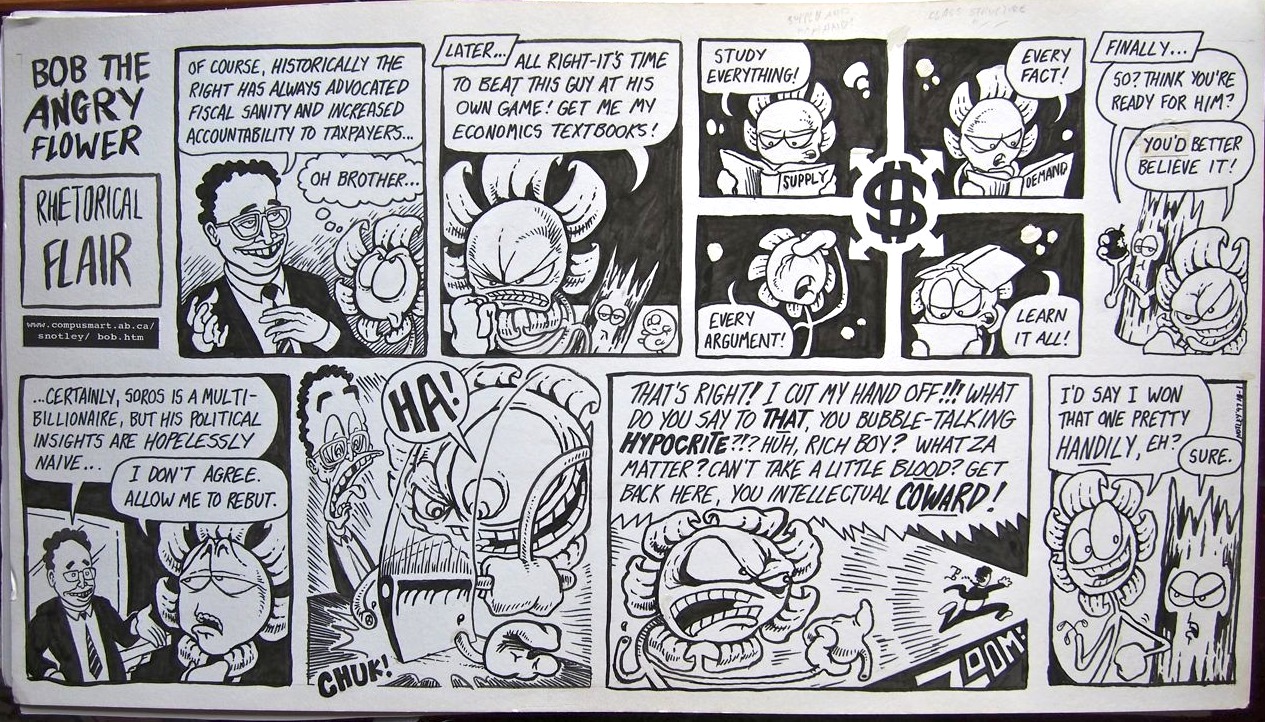

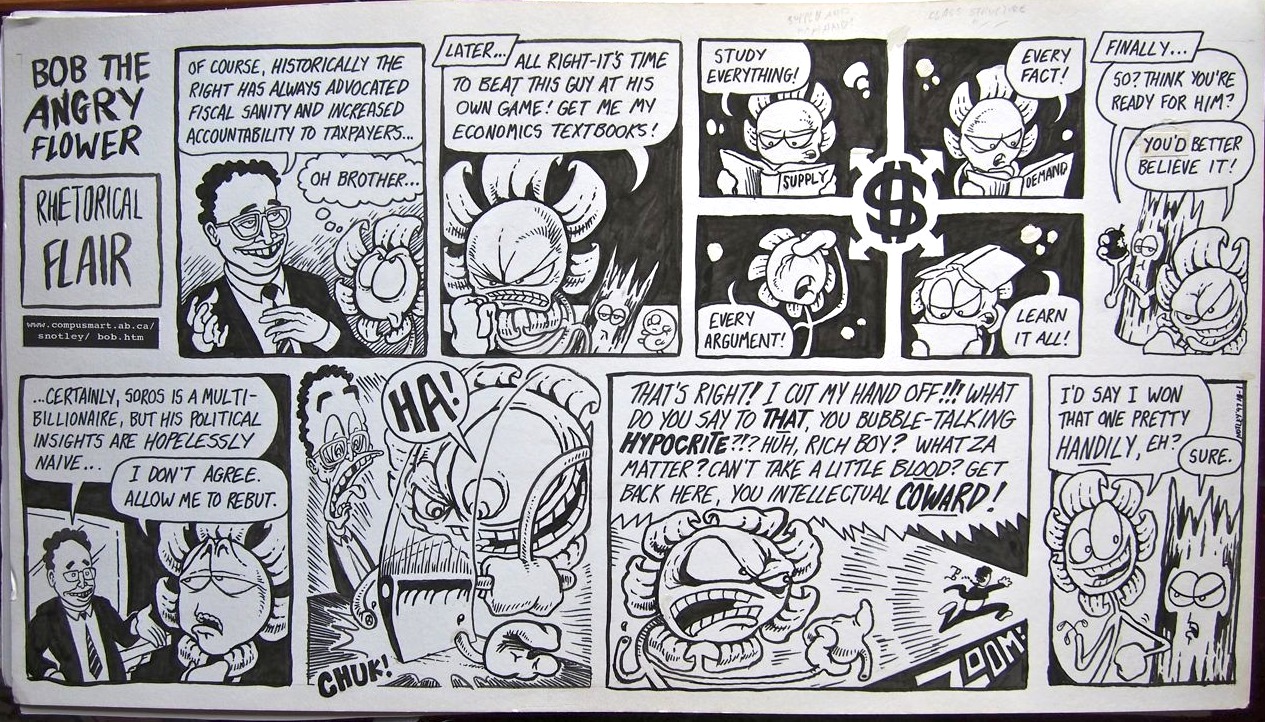

At some point during those years I came across Stephen Notley’s brilliant Bob the Angry Flower. One comic, called “Rhetorical Flair,” especially spoke to me.

I recently contacted Notley about buying the original art, and soon afterward it showed up at my house. And it’s great! It’s much larger and more awesome than I had any right to expect. Check it out:

|

|