By Mike So, seeing the apoplectic outrage of the right wing about losing the filibuster in certain limited situations (an overdue rap on the knuckles considering how the filibuster has been abused in recent years), I thought I’d repeat something from a post I made two years ago during the first bullshit debt limit crisis. That post makes a bunch of points, but today I’ll just focus on one:

The idea that the filibuster was somehow envisioned by the framers of the Constitution? That’s completely wrong, according to the Federalist Papers, which is the best source we have on what the framers were thinking.

Here’s the key passage:

To give the minority a negative [i.e., a veto] upon the majority (which is always the case where more than a majority is requisite to a decision) is in its tendency to subject the sense of the greater number to that of the lesser number. . . .This is one of those refinements which in practice has an effect, the reverse of what is expected from it in theory.

The necessity of unanimity in public bodies, or of something approaching towards it, has been founded upon a supposition that it would contribute to security. But its real operation is to embarrass the administration, to destroy the energy of government, and to substitute the pleasure, caprice, or artifices of an insignificant, turbulent, or corrupt junto, to the regular deliberations of a respectable majority.

In those emergencies of a nation, in which the goodness or badness, the weakness or strength of its government, is of the greatest importance, there is commonly a necessity for action. The public business must in some way or other go forward. If a pertinacious minority can controul the opinion of a majority respecting the best mode of conducting it; the majority in order that something may be done, must conform to the views of the minority; and thus the sense of the smaller number will over-rule that of the greater, and give a tone to the national proceedings. Hence tedious delays—continual negotiations and intrigue—contemptible compromises of the public good.

And yet in such a system, it is even happy when such compromises can take place: For upon some occasions, things will not admit of accommodation: and then the measures of government must be injuriously suspended or fatally defeated. It is often, by the impracticability of obtaining the concurrence of the necessary number of votes, kept in a state of inaction. Its situation must always savour of weakness—sometimes border upon anarchy.

Take the time to read that. “Embarrass the administration.” “Destroy the energy of government.” “Contemptible compromises of the public good.” “The measures of government . . . injuriously suspended.” “[Government] kept in a state of inaction.” The framers thought that the Constitution would avoid these problems, *because* they set things up so that the majority would actually have its will done. They not only didn’t institute the filibuster, they thought they had safeguarded against such things.

That’s not how things have played out.

It’s not that I think that the framers’ intent is an infallible guide to modern problems (see: three-fifths compromise). But if you disagree with them, say so. Don’t claim that they agreed with you when they clearly stated the opposite.

EDIT: I should have mentioned: The fact that the framers rejected the need for a supermajority (except in very specific cases) means that they put their safeguards against ill-considered government action elsewhere, like the fact that both houses plus the president have to agree on a law. Adding more “safeguards” on top of these is a recipe for all the problems above.

By Mike I freelance, but I’ve been fortunate enough to be able to afford private health insurance since I was in my 20s.

I thought my premiums–north of $7,100 per year now, and I’m single with no children [EDIT: And no health issues]–were pretty ridiculous, especially because I was on the absolute cheapest option my plan offered (no dental, big deductibles, etc.). Still, this was real insurance, not junk insurance, and there weren’t much in the way of better options out there (I checked).

Then I got a note from my provider that because of Obamacare, my plan would have to change. And that I would get another note with the new offerings soon.

I still haven’t received the new offerings, but I checked with another provider to see what they would sell me; its a safe bet that their deal will be pretty similar to my current provider’s. So let’s check them out.

The new plan only has one offering that’s even as expensive as my current plan (the cheapest, remember), and that covers pretty much everything. The cheapest offering, which is similar to my current one, is $4320 per year.

So, in the post-Obamacare dystopia, I can save almost $3,000 per year for similar insurance, or get much better insurance at the same price.

Let that sink in. Under the Affordable Care Act, my costs are nearly halved.

Of course, that’s the situation in New York; I don’t know how things are going in other states. Still, New York is a big state, and a lot of other people will be seeing that sort of improvement, *without* subsidies.

And yes, I don’t know what my current plan will be offering. But if it’s not at least as good, I can switch. Imagine that–healthcare that you can switch without worrying that if something goes wrong, and you lose coverage for a minute, you’ll never get it again for the rest of your life.

One last thing: There’s a pie chart showing Obamacare’s winners and losers making the rounds (one source here):

On that chart, people in my situation don’t count as winners. We fall into the “no real effect” or “potential loser” categories.

So yes, Obamacare is a freaking Rube Goldberg machine, and single-payer would be simpler, more just, and cheaper. But at least in New York, at least for people like me, *it has nearly halved premiums.*

That ain’t nothing.

By Mike So, Economix will be getting a Greek translation.

And apparently the Greek market likes color comix, so the publisher will be putting Economix out in color!

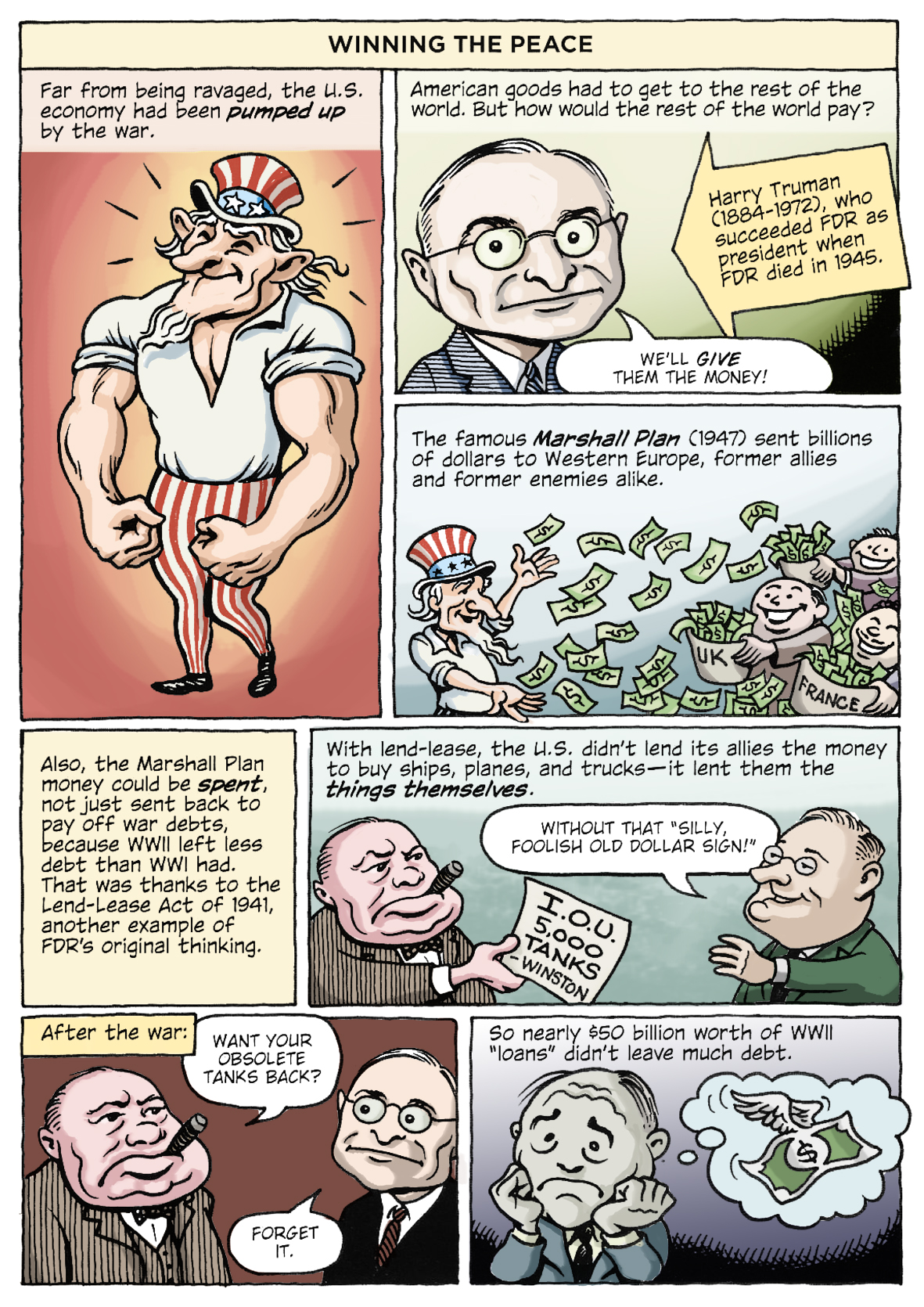

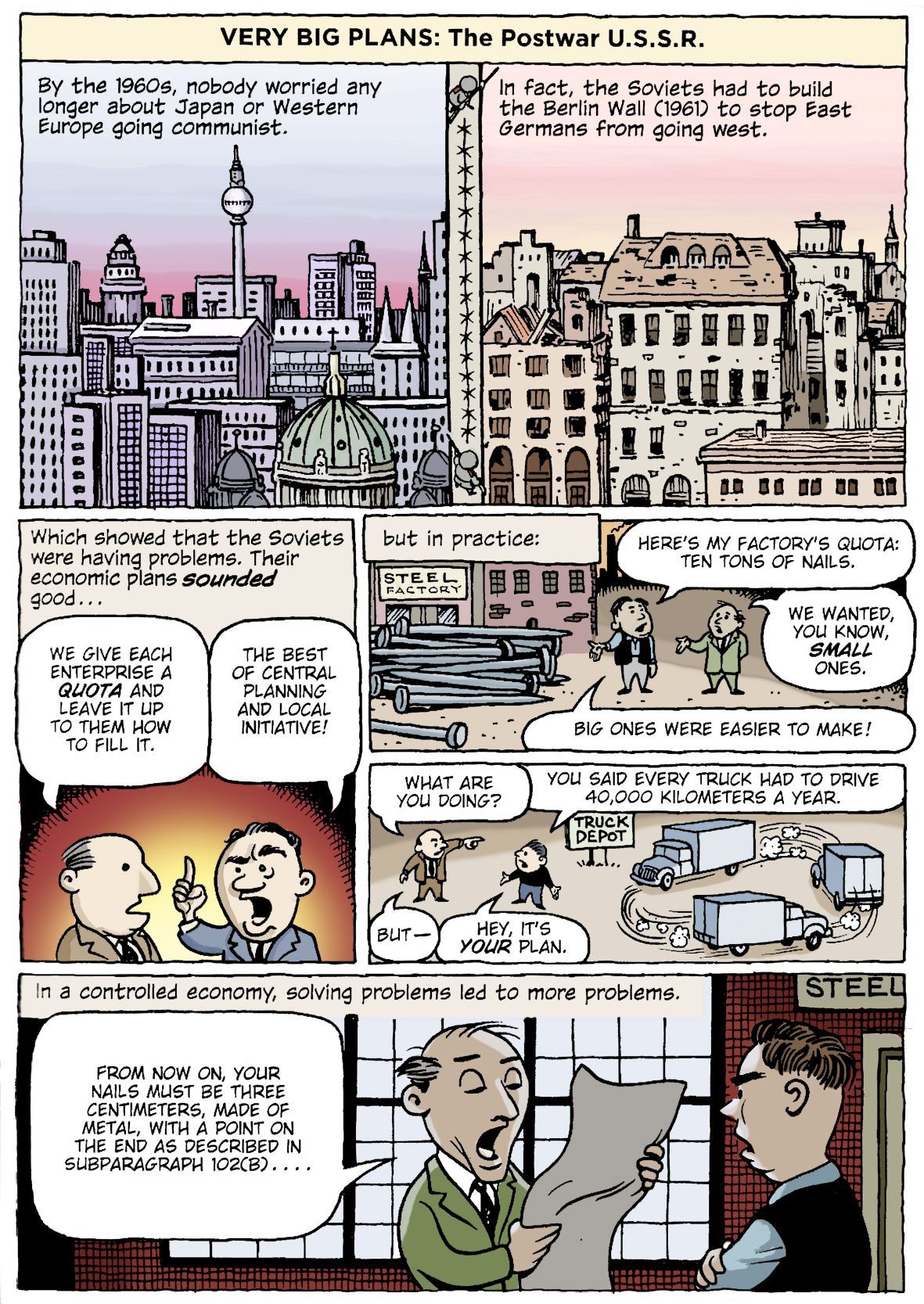

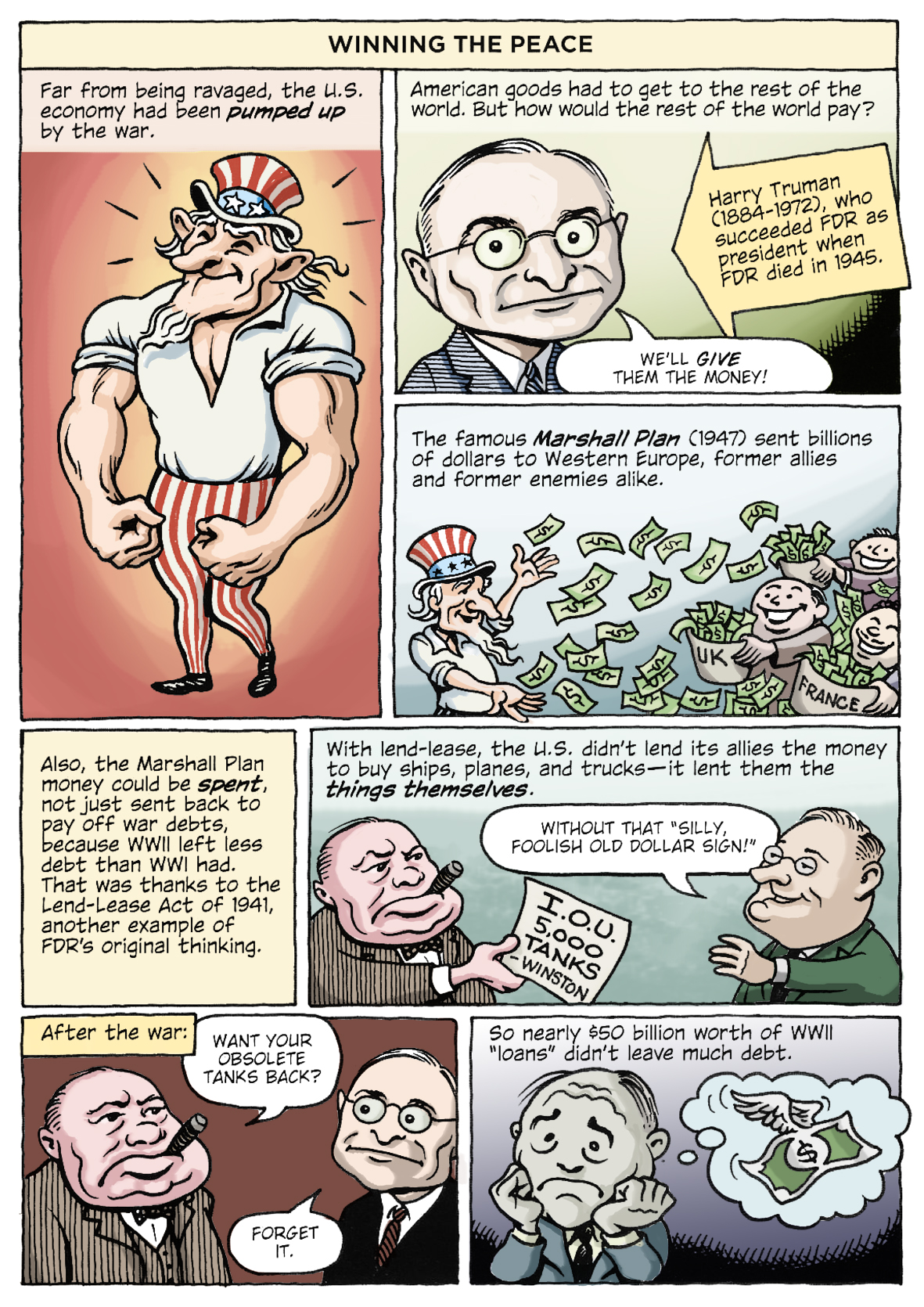

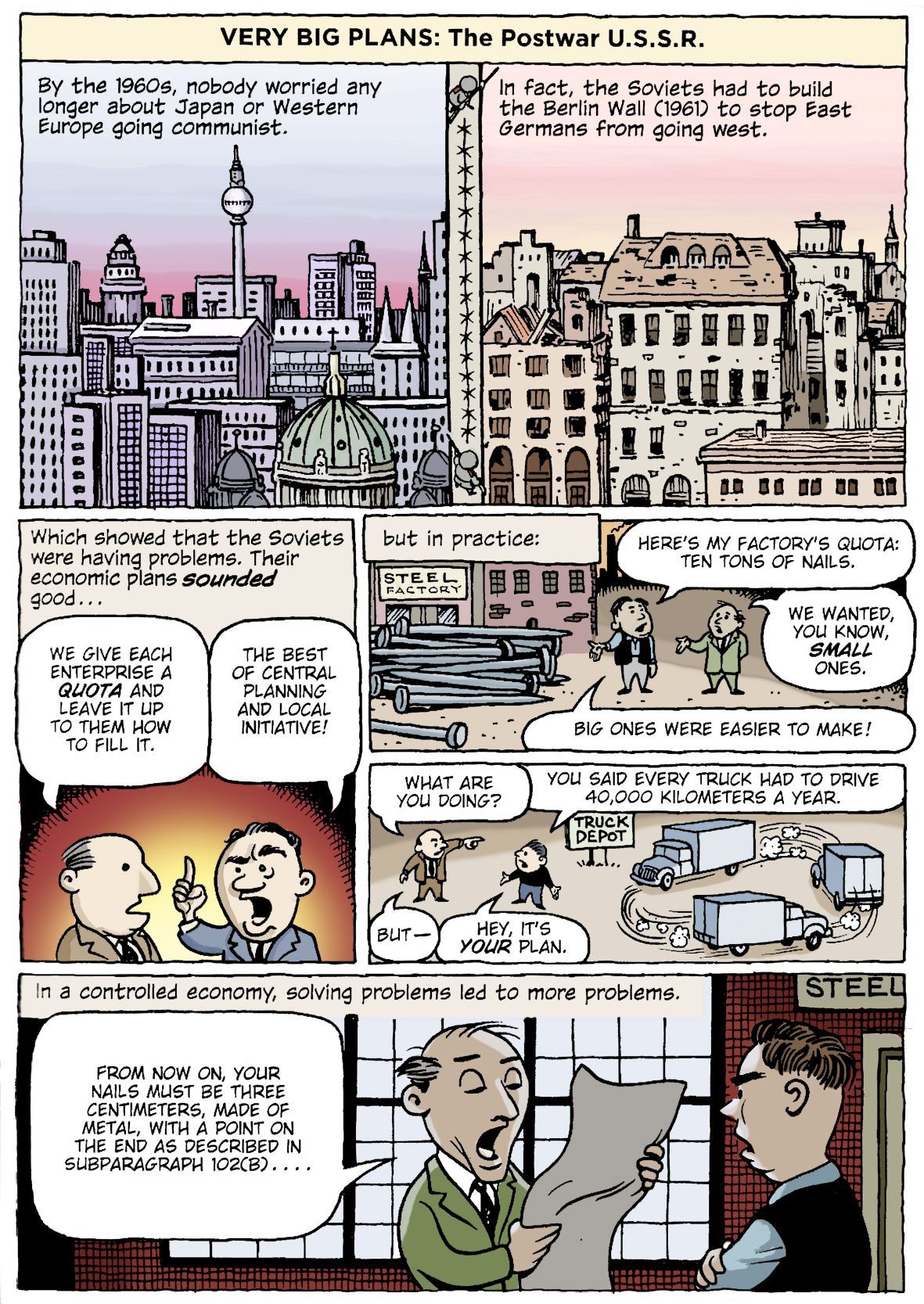

I was skeptical at first—we used black-and-white by choice, for clarity—but I’ve seen some sample pages, and they look good! Check them out:

By Mike If you go to the Heritage foundation website, they’re throwing everything they have against Obamacare. “Everything they have,” if my nonscientific I’ll-read-all-I-can-before-I-vomit sampling is any indication, comes down to three things:

- Some people are quotably scared of Obamacare. Which is not exactly surprising after a multi-year smear campaign (remember “death panels”?).

- It’s the thin end of the wedge for true single-payer healthcare. I wish. God I wish. Better results at lower cost? Oh noes!

- Some bad things (like people’s choice of doctors being limited, which has been the case for me with private insurance my entire adult life) will continue happening once Obamacare is implemented, and this is somehow the fault of Obamacare and will be forever from here on out.

What Heritage doesn’t give is an alternative. Which is no surprise. Obamacare is their alternative.

So, conservatives said, in essence, don’t try single-payer, we have a way to make our current system work. Obama said okay. Then they fought him every step of the way, and now they’re going to shut down the government rather than see him get the credit for its success, modest as that success will be.

This is why we can’t have nice things.

Once Obamacare is operational, I’m interested to see what happens next. Do Republicans try to take the credit after all? Do they keep smearing it even as it works? Do they admit they were wrong about something?

I’m not holding my breath on that last one.

By Mike So, I did some more digging after my post talking about performance-based pay.

(The relevant points from that post: The government does not allow companies to deduct pay over $1 million for execs, but “performance-based” pay is excluded, which is why so many execs get “bonuses” no matter how badly they do their jobs).

It turned out that I’d made some errors in that post (edited now, with edits marked), but I also turned up some interesting news:

- In August, Senators Jack Reed (D-RI) and Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) introduced a bill to close this loophole.

- Closing this loophole is estimated to bring in $5 billion per year.

Okay, $5 billion doesn’t seem like much in the grand scheme of things. But remember Republicans’ brutal $40 billion cut in food stamps? That’s $40 billion over 10 years. Or $4 billion a year.

In other words, the Food Stamps cut, which has been presented as a necessary sacrifice in the name of fiscal responsibility, will save less than simply not subsidizing excessive executive bonuses.

No doubt, a party so deeply committed to fiscal responsibility will support Reed and Blumenthal’s bill. Right?

By Mike So, this year’s SAT scores are out, and they’re disappointing. Only 43% of students who took the test got scores indicating readiness for college.

Really, SAT scores have been flat, or even slowly falling, for a while. Some of that slow decline can be attributed to more people taking the SAT. Maybe all of it can. But scores clearly aren’t getting better. And that’s really disturbing.

Why, you ask? Because at this point the kids taking the SAT have spent more or less their entire school career in an education system governed by No Child Left Behind, which puts an insane emphasis on standardized tests. Kids must be better at taking tests after all that practice. So if they’re not scoring any better, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that everything except test taking has gone downhill.

Why are we sticking with No Child Left Behind, again?

By Mike So Robert Benmosche, the CEO of AIG, is under fire.

AIG, remember, took a bunch of very stupid bets on the mortgage market, needed a massive bailout from the government (a bailout that was really a gift to the companies that took the other side of AIG’s bets, like Goldman Sachs), and then paid its executives big bonuses for the fine job they did receiving government money.

There was more than a little outrage about that, which Benmosche thinks is “just as bad and just as wrong” as “what we did in the Deep South.” You know, things like this (disturbing image alert):

…

…

…

…

…

…

The thing is, not only does he think that–in a truly spectacular own goal, he went on record saying it.

This is more evidence that, to quote a previous post, financiers are dangerous idiots who have to be watched every minute.

But that wasn’t even the stupidest thing he said. That distinction goes to this (same link):

[Critics referred] to bonuses as above and beyond [basic compensation]. In financial markets that’s not the case. … It is core compensation.

Of course, everybody knows this. “Bonuses” on Wall Street are part of the package as much as salary is. One big reason for that: companies can’t deduct more than $1 million in salary [EDIT: For top executives] as a business expense, but performance-based pay is excluded. This law, which dates from the 1970s [EDIT: 1990s], has had exactly the effect you would predict: companies give bonuses and say they’re based on performance, when really the “bonuses” are automatic. (The amount of the bonus can vary with performance, but there’s almost always some bonus–like overindulged toddlers, Wall Street execs live in a world where everyone gets a prize.)

This amounts to a subsidy for excessive pay, from taxpayers to overpaid executives.

The thing is, it’s always been crucial to pretend that bonuses really do depend on performance and it’s just a coincidence that executives perform so superlatively every year, even as their companies look to outsiders to be falling apart. If anyone ever admitted to giving their executives bonuses that don’t depend on performance, why, that person would also be admitting to tax evasion.

And when Benmosche said that bonuses were core compensation, that they were not above and beyond basic compensation, that’s exactly what he did.

I’m assuming, of course, that AIG does deduct bonuses for its execs as a business expense when the total compensation goes over $1 million. That seems a safe assumption, although I can’t think of how to check it.

Apparently the Superintendent of Financial Services of New York is “in touch with AIG about Mr. Benmosche’s comments“; the nature of the communication isn’t given, but here’s hoping that that some AIG execs, including Benmosche, wind up in jail for tax fraud.

If not, well, the time for pitchforks and torches may yet come.

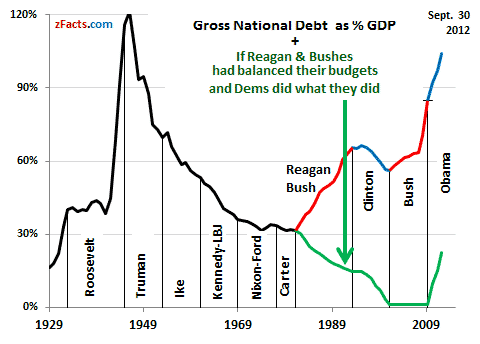

By Mike It’s worth mentioning that when I came across the chart in Monday’s post, I wasn’t just idly sifting through charts; I do have a life. Rather, I wanted to check to make sure my understanding of the history of the national debt was right.

My understanding was:

- When Ronald Reagan took office, the burden of debt was low; it had been falling since the end of World War 2.

- Reagan and then Bush drove up the debt

- Clinton brought it back under control

- Bush II drove it back up again, and left us with a persistent depression that has kept its burden increasing.

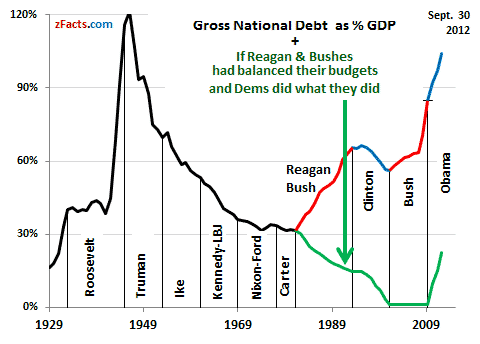

And yep, that’s what happened. Here’s the chart again (ignore the green line, which is dumb):

So why did I even need to check that? It’s pretty freaking obvious, right?

Well, I checked after I read, in a source that shall remain nameless (it’s a typical economics-for-laypeople text):

“During World War II, the national debt soared to over 100% of GDP. Then it was pretty steady at 30%-60% of GDP for 50 years. And after the 2008 financial crisis, it’s heading back up toward 100%.”

That’s technically correct, but it’s so far from the actual story that I had to go and make sure I wasn’t misremembering what actually happened. And no, I’m not quoting out of context: That passage contains everything the source says about the subject.

I’m not trying to single that source out. It’s one example of a serious problem with almost all economics instruction (except, ahem, Economix): The idea that economics is somehow above partisan politics.

There are a lot of problems with that. One, it’s misleading. Someone reading the above example would think that, aside from the pesky 2008 crash, everything was basically hunky-dory with our debt.

Two, it’s dull. Dull, dull, dull. Seriously, read that example again. It turns an interesting story into a recitation of meaningless facts. Is it any wonder that most people find economics boring?

But most of all, and the reason I wrote this post: it’s political. Avoiding politics will keep a textbook noncontroversial, the better to serve its tepid dishwater to more students, but when (to pull an example out of the air) certain politicians take out trillions in our name and leave us with nothing to even show for it, not mentioning this is not just highly political: It’s straight-up partisan. More partisan, even, than just giving the story straight.

I understand why avoiding politics seemed like a good idea back in the day. But it hasn’t worked out as advertised, and it’s time to stop.

Fortunately, economists are starting to wake up to the problem. But it will be a long time before that seeps down to the level of the typical econ 101 text.

But hey, until then, there’s Economix!

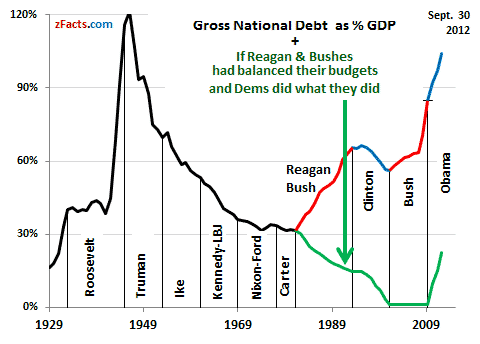

By Mike So, I was looking for a chart showing the national debt over time and came across this one, from zfacts:

Debt as a percent of GDP is the best measure of the actual burden of the debt; the economy (i.e., GDP) is where any funds to service or pay back the debt have to come from. And this shows what everyone not in the conservative parallel universe knows: The burden of the debt shot up for WWII, then came down sharply, and was still on its way down when Reagan took office (ironically, running in part against the debt). At that point it zoomed up until Clinton took office, when it leveled off and came down a bit (not that Clinton actually paid any of the debt off, but he did stop its growth, so as GDP increased the ratio decreased). Then George W. Bush took office and the debt zoomed again.

A lot of charts show this, but this chart had some info that I’d never known before. I’m not talking about that green line—that’s partisan hackery. There’s no reason that Reagan and the Bushes should have balanced their budgets, as much as they may deserve to be impaled (exhumed and impaled in Reagan’s case) for taking out so incredibly much debt in our names.

I’m talking about the line all the way to the left–the one that shows where Roosevelt took office (1933). I’d never realized how high the debt-to-GDP ratio was at that point. It’s higher than where it was under Ford and Carter.

In other words, in 1980, after the huge expense of World War 2 plus thirty-odd more years of liberal, free-spending government (with conservative complaints about the debt as constant background noise), the burden of debt was lower than it was when Herbert Hoover left office.

This is yet more evidence against the idea that the way to deal with debt is by cutting spending. I only wish that evidence mattered in today’s economic debates. . . .

By Mike The Syria situation is a freaking mess, and I’m not even going to add my two cents as to what we should do.

But I do have something to say about *how* we come to a decision:

One of the less savory aspects of the rush to war in Iraq was the way that, in the incestuous world of our political class, many of the pundits who called for war had serious conflicts of interest, conflicts that were not even disclosed.

So George Shultz was presented as a “former Secretary of State,” not a former president and current member of the Board of Directors of Bechtel Corporation, which stood to profit mightily from the Iraq war. (And did.)

And Richard Perle didn’t bother to reveal his connections to Trireme Capital, a defense- and security-related company, until Seymour Hersh (one of our last actual investigative journalists) helpfully did it for him.

You’d think we’d have learned. But according to the blog North Decoder, we haven’t. Specifically, North Decoder caught retired General Michael Hayden calling for an attack on Syria (on MSNBC) without mentioning that he personally stood to profit (and without being called on it).

Seriously, what the hey? Haven’t we learned that when we face the grave and potentially catastrophic decision of whether or not to go to war, we shouldn’t listen to arms dealers? Or at least, if we do listen to them, we should *identify* them as arms dealers?

|

|